‘You can have a whole website full of lip service, and you still have students who experience racism…’

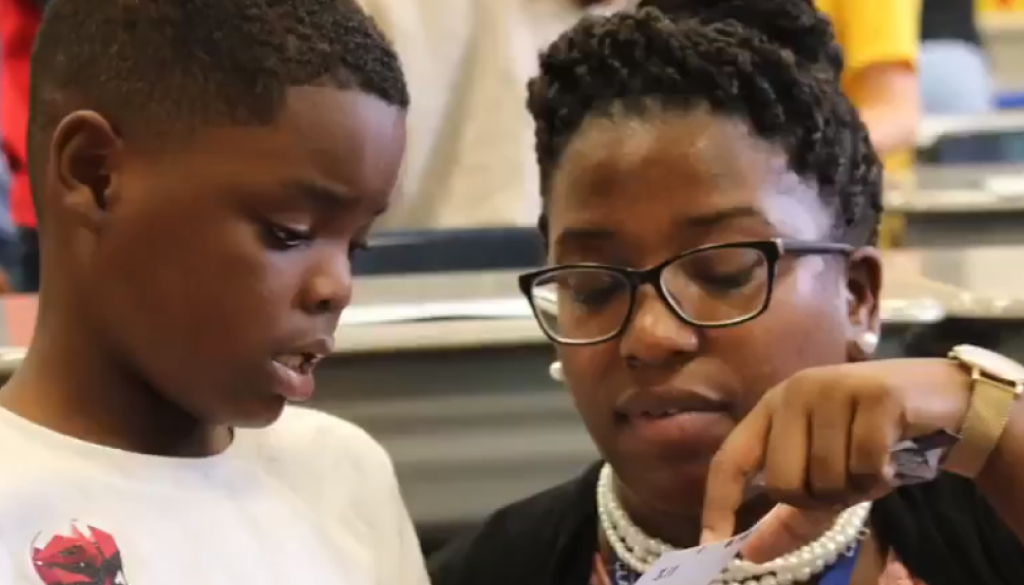

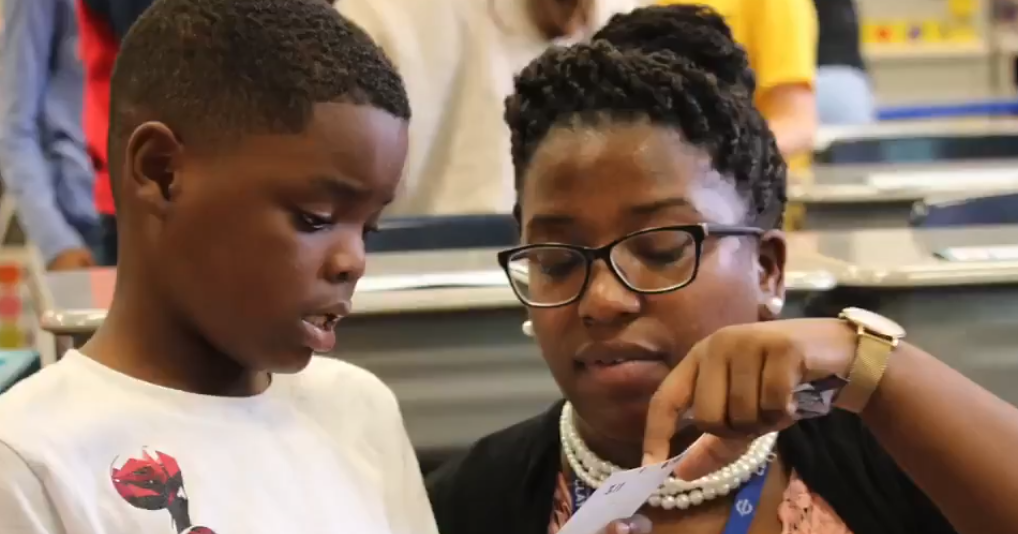

Photo by Robin Fultz/Clayton School District

Jalita Johnson taught second grade for two years at Captain School and is leaving the district because her husband has been transferred to a job out of town. Johnson, 29, and a native of Macon, Ga. taught in the Normandy School District before coming to Captain in 2018. She consented to an hour-long interview with Richard Weiss concerning the challenges she faced in her job.

Richard Weiss: How did you become interested in teaching in the Clayton district?

Jalita Johnson: I was at a math conference and met what was then the math specialist at Captain School. We were talking equity in math, and he mentioned that I should apply for a teaching position. By that time, I only wanted to be dedicated to Normandy, because I knew it was a high needs area. But he convinced me that there were students in Clayton who would benefit from my work, as well.

Weiss: So, you went from a majority African-American school. Maybe I shouldn’t even say majority, it was all students of color, right?

Johnson: Yes.

Weiss: What was the racial makeup at Captain?

Johnson: I would say about 70% white and 30% multi-race. It was a big difference from Normandy in all respects, in terms of funding, resources, leadership.

Weiss: When you first got going, how many other African-American teachers, or teachers of color, were at Captain?

Johnson: At Captain? I was the only one.

That was one of the biggest things that woke me up to the true essence of Clayton, because I was so optimistic and enthused based on the hiring process and the way the district would say, “We’re hiring you to grow us.” It was all around optimism and enthusiasm for what was possible. But I quickly realized I was the checked box.

Weiss; You must have had some experiences or some things that were said or done that would make you say that made you feel that way.

Johnson: Well, my family and I experienced micro-aggressions. And that was in the community. Because when they hire you, there’s this thing that you should not just want to teach, you should want to be a part of the community. Well, we couldn’t afford to be a part of the community, so we would travel in and attend different events, because my children were at the family center. And so once I started picking up on those micro-aggressions and racial undertones in the community, I started to become aware of what that looked like in school.

Weiss: How did that play out in school?

Johnson: I was approached one day by a colleague who said she could tell that I had an enthusiastic teaching style. I like to move around. I like to use my hands when I talk, and I like to use my tone of voice, whether I’m trying to put a joke across or be funny or whatever, in interacting with the kids. And she explained that this coming from a Black female teacher it could be overwhelming for some students. As I started to get critiques and observations, it was more or less, now, we need you to model the behavior of a middle-aged white woman. And I couldn’t understand that at first.

Here’s another example to give you context. Every day at school is a letter day. The first day of school for me was a B day. And you have art one day a week, and library one day a week. Well, I just so happen to have art and library on the same day, and that was the first day of school. So that means, instead of science or social studies, the kids will spend an hour in art, and instead of a full hour, of literacy, they’ll spend half of that in the library. And so while I was in my first day at a new district, in a new school environment, I had to get the kids adjusted to that type of movement on the first day of school.

And one of the things that wasn’t explained was the idea of snacks. In my mind, coming from Normandy, the kids would be served lunch at 11:00 and there was no food, no drinks in the classroom, and they went home at the end of the day. And that was it. And so coming to Clayton it was a situation where, “Okay, guys, you have to pack up, because we have to go to art and library, so you’re not going to have a chance to get back in to the classroom.” And I didn’t know that I was supposed to make time for snacks, but one of the kids knew that they were supposed to have snacks, and mentioned to their parents that they didn’t have snacks. And instead of coming to talk to me, the mom went straight to the principal, and, of course, the principal called me into her office. The first week of school, and it was very demoralizing. And another parent got wind of it, asked their child, “Did you have snacks?” And of course, she said, “No.”

So she went to the principal. And it was just one of those things where I couldn’t help but think something so minuscule should have been able to be brought to me. I don’t feel anger for it. Just figuring out, they didn’t know how to approach me about it,

Weiss: So you feel like if it was a new, white teacher, you think they would have gone to her directly, is that what you’re saying?

Johnson: Of course.

Weiss: And what did the principal say about all this? Did she respond appropriately?

Johnson: It was never a reprimand type thing, but for me, because I was always the goody two shoes in school. I had to have As. I had to be perfect, and so the idea of going to the principal’s office my first week on a new job, was just like ugh. The way she questioned me, you could understand that she took the parent’s concern seriously. It isn’t as if I expect the principal to defend me, but maybe her first question to the parent might have been, “Have you talked to the teacher about it?”

And then if you don’t get any answers that way, then you come back to me. But that wasn’t the case. It was like, the parent told her what they needed to say, and she talked to me. I never got a chance to explain to the parent and the principal what happened so there could be some type of clarification. It was just one of those things where I just had to keep it moving, and hope that things got better.

Weiss: And did circumstances get better?

Johnson: No.

Weiss: It must have been kind of a lonely feeling that you were dealing with this and there’s no other African-American staff member at the school to talk to or commiserate with. Is that hard?

Johnson: No. Not because it was one of those things where internally you feel justified in your anger or your frustration, but once you verbalize it to someone you hear how small it is, so you shouldn’t let it get to you. But that is a nugget of the bigger picture at hand with micro-aggressions and how a supervisor can be culturally responsive to someone who’s the only Black teacher in the building. You need to have someone understand that a teacher might feel slighted because they didn’t give her a chance. But after two years of talking to other teachers, I found this was a common thing. That parents knew how to pull the levers of school leadership, and bypass the teachers. And there was no culture within this district to redirect parents to go talk to teachers. It was always, what a parent says, the district does.

Weiss: So you adjusted.

Johnson: Yep. And that’s kind of, a long story short, how I ended up being so close to the parents now. Because I learned early on that anything that needed real substantive change in the district needed to be spearheaded by parents, because they wielded the most power.

Weiss: Tell me a little bit about your relationship, to the extent that there is one, with the parents who are pushing hard on racial equity.

Johnson: Yeah, Laura (Horwitz) was one of my parents in my first year. Again, there were a few squeaky-wheeled parents, if you will, who made the experience negative, but she was one of the parents who I would call, the silent majority, that had positive experiences and wanted to know how they could help or be of assistance with getting acclimated to the area or to the community. And so we connected over her work, when she was then a part of an organization called, We Stories.

Toward the end of the school year she was talking about how she wished she had known that I had so many issues in the beginning, because she would have been more vocal. Because parents were also going to her asking, what did I need? And how could they be of assistance? Again, instead of coming to me and asking me. She was kind of the voice behind the parents.

Weiss: I wonder if they were just feeling awkward about dealing with an African-American teacher.

Johnson: Yeah, I guess….

Weiss: … and maybe they were sensing you were uncomfortable, they didn’t want to make you even more uncomfortable.

Johnson: And that’s why it’s important for inclusion and diversity, because there’s this thing called the Clayton Bubble that I was aware of before applying. And it was very obvious when I first started working that some of them had not experienced an African- American teacher, let alone someone whowas in charge of their kids, per se.

Weiss: What is it that needs to happen to, I guess, pierce the Clayton Bubble? Laura is part of a group of, I think it was, eight parents who put together a list of demands. Have you seen that?

Johnson: Yes.

Weiss: Did you give them some advice on what to put in there? Or what was your position?

Johnson: I wouldn’t say I gave advice, but I did provide feedback. Because one of the things that, I think, I was able to conceptualize based on being someone from outside of the bubble and coming in and just noticing how everything was working from the board all the way down to the school building. There is a group of community members that does wield power because of the resources they have at their command – financial and otherwise. And you have the parent groups like Laura’s who have been advocating for the transfer program from Normandy, and inclusion and diversity.

But then you have this other group of community members and some parents who want to keep their precious resources to themselves. And the board and the district pays lip service a lot around inclusion and diversity, but there’s no real action.

Weiss: The problem you describe isn’t just in Clayton, right?

Johnson: Well, it’s just the way that our country is created around education. It dates back to the era of segregation. When you consider red lining and zoning and districting, people with privilege have the ability to say, “This is our little area. And our tax dollars that are valuated at a certain amount, due to our privilege, goes to this school, and I don’t want anyone else to have access to it, because I worked for this.” That is the downside to our country, so I can’t just say, Clayton, in particular, is this stand-alone city that does this. This is indicative of the bigger picture around resources in schools.

We need to do a better job at helping every stakeholder identify their privileges and how it in turn perpetuates that inequity, whether it be in the bubble or outside of the bubble. Because what a lot of people fail to realize is if you keep your healthcare to yourself, if you keep your education resources to yourself, and you only want that to go to your children, eventually, your children are going to grow up and be in a environment with those kids who did not have access to those resources. So they’ll still be affected either way.

You can have a website full of lip service and you still have students who experience racism or parents or teachers for that matter.

Weiss: Did you ever have any interactions with the top administrators, assistant superintendents and superintendent?

Johnson: I shared it so much within the building that I never felt it necessary to go to Sean (Doherty), because this is no slight to him, but I just didn’t feel like there would ever be anything to come of it.

Or if it was a situation where I did express it on the building level and nothing was done to my satisfaction, it would be, probably, viewed as anger or frustration or sidestepping my building leadership if I did take it to him.

That has to be reserved for what is serious and sensitive, so that’s where you’d get into having to be resilient as an African-American person. Whether you are a student or a teacher, you have to have that type of of shield where you understand, I can’t really say or do anything about this, because it wasn’t so extreme that anything could be done.

For example, I had an instance where a parent approached me and in all honesty, looking back on it, she probably had no idea that what she was saying was problematic.

But she came in and basically explained that her daughter wanted to be me for Halloween and they had a conversation about black face. And she wanted me to talk to her daughter about why that wasn’t a good idea. And I don’t know, I was just taken aback by it as a parent, I felt like that should be a fairly obvious or an easy conversation to have with your daughter about why that’s not appropriate.

And then expressing that with a colleague I received a response, “Well, she’s just a kid. I don’t understand, what’s the problem?”

Johnson: And it’s like, is that a serious enough issue that I need to go to Sean or I need to go to the principal about it? What can actually be done about that?

Weiss: And you’re thinking: Why should it be my problem to speak to the daughter about this…I/

Johnson: Or my burden to explain.

So that’s just an example of how there were always things coming at me… To your first question about did I ever talk to district leadership, it’s like, how do you explain all of these small cuts to district leadership? What do you really expect them to do? And that goes to my passion for the work around the parents’ petition. It’s like getting everyone from district leadership to building leadership to understand the nuances that perpetuate this system of inequity or not really including everyone.

So that was why I felt it necessary to be a voice in the petition. But again, I’m kind of pessimistic in the same sense of knowing the way the district works, and that’s why I pushed the parents to stay with it. Even if this falls short or doesn’t come to fruition right away, stick with it.

Weiss: Did you read what is essentially a statement of contrition on the part of the superintendent that he put out there? How did you feel about that?

Johnson: Everyone from the top down have this perfect ability to use language and you could tell the superintendent listened, but you can also tell that he’s not really going to take it as seriously as he should. The district is more on the side of catering to white fragility than they are to making the radical change necessary to make sure everyone is included, and not just playing lip service to it.

The idea of even being a district that includes others or is proud to say they include others, drew me to Clayton. So for me it is one of those things like James Baldwin put it. He said he loves America and because of that he has the right to criticize.

And I love Clayton, that’s the district that’s on the right path, but they’re not perfect. And I would never say, “Clayton is a horrible district.” It’s just a district that needs to be critiqued, and through that criticism, they can go on to be bigger and better for all students, and not just a particular subset of students.

So out of three years, the district has probably moved three inches. The accountability is not there.