By Erika Whitfield

Let’s be clear. Banning books is not about protecting the innocence of children.

Book banning is about conservative control. That control is often masked in arguments pretending to protect children from explicit material. In fact, most book banning efforts are focused on the stories of Black, Brown, and Queer folks that challenge the patriarchy. Books under assault include dystopian plot twists that include religious regimes taking over the government and controlling who has access and control of the dissemination of information and of women’s bodies.

None of that seems far fetched in these times.

One might conclude that when the dominant culture is not centered, it can make conservative white people uncomfortable.

I have a personal experience with this stemming from my work in the fall of 2018 at Christ Light of the Nations, a small St. Louis Archdiocesan school in Spanish Lake, which is now closed. When I first started teaching at Christ Light. I was so excited to introduce students to more diverse texts. The school had a predominantly Black student enrollment, but most of the teachers were white.

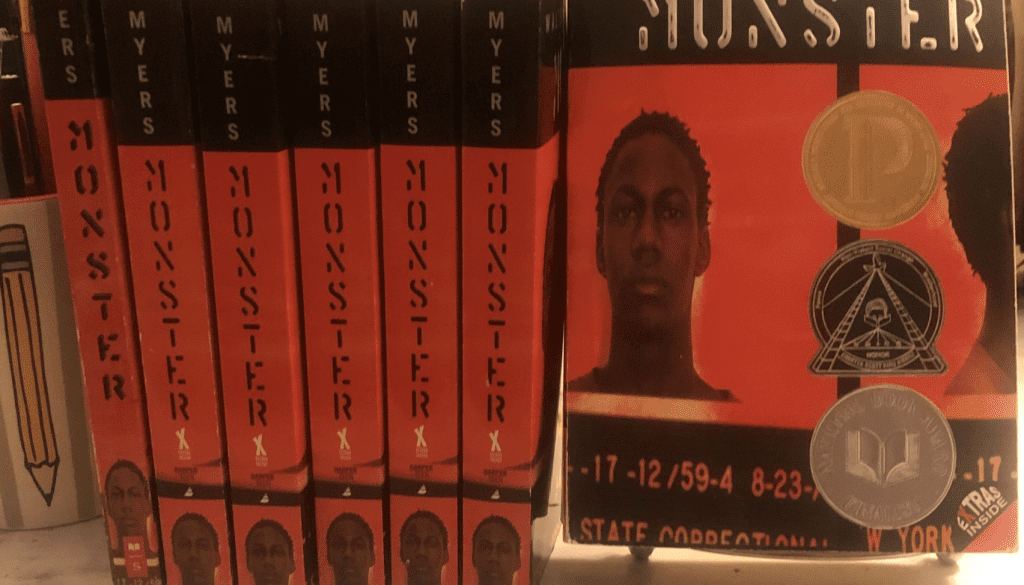

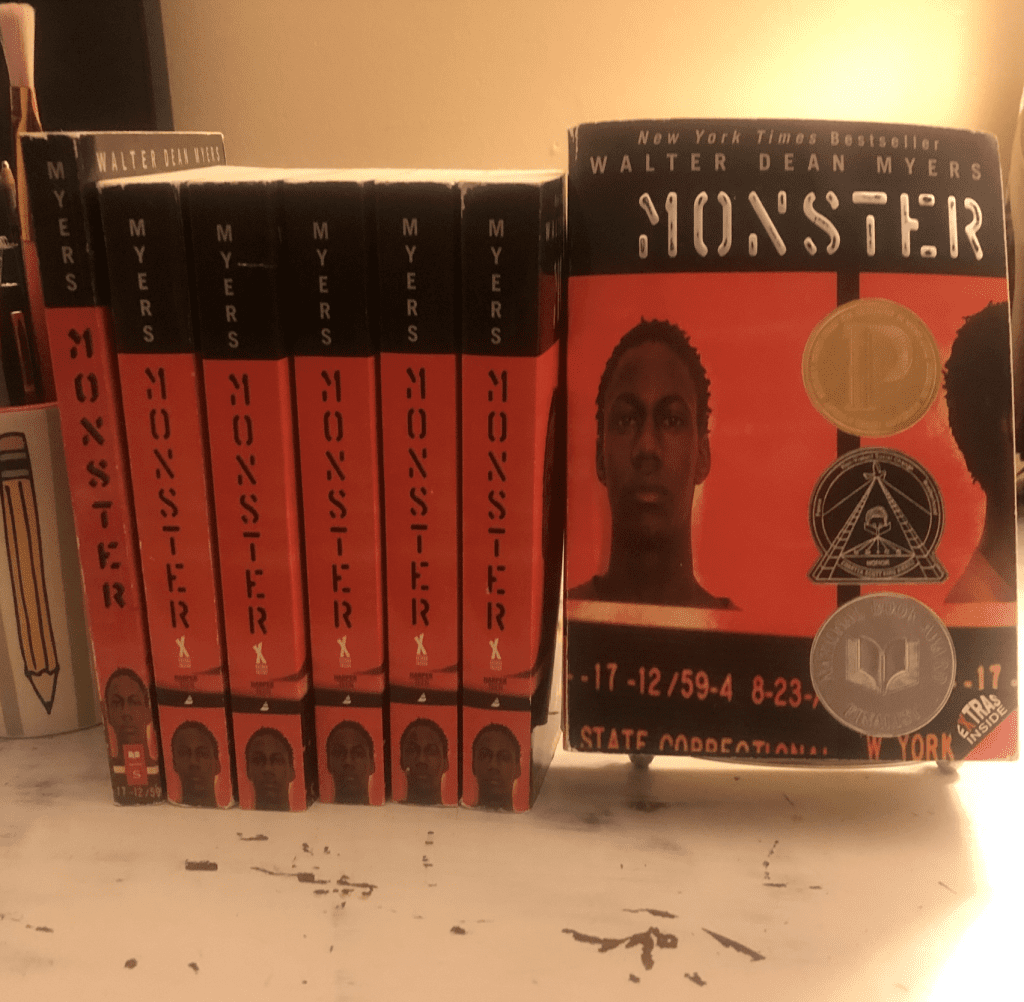

I mentioned to a colleague and longstanding teacher who’d taught both social studies and language arts, how excited I was to read Monster by Walter Dean Myers. I proudly displayed my class set of books ready to distribute to students. She informed me that a few years prior, parents were up in arms about the book because it mentions rape in prison. It doesn’t describe it explicitly. The school did not have a list of banned books, but it was made clear to me that certain subjects were taboo.

Bottomline, I could not read it with my students. That was the first time I’d experienced the prospect of parents controlling what books students could read in my classroom. This wonderfully inventive novel is told from the perspective of a 16-year-old black boy who finds himself in jail waiting his trial for being an accomplice to a crime. With no criminal history, and a stellar reputation, he finds himself fighting for his freedom. Myers is considered one of the greatest youth writers of our time. Monster won the Michael L. Printz Award, a literary honor, and it was a New York Times bestseller. I could not share it with my students. Instead I taught A Long Walk to Water by Linda Sue Park.

Now as a high school English teacher at a public school and with even more experience, I see banning books as a tool to silence diverse voices. We can not just read what makes people comfortable. Perspective is vital and aids in understanding especially as it relates to race and gender identity.

In a diverse world, we must have diverse texts. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of We Should All Be Feminists and Half of a Yellow Sun, warns of “the dangers of the single story” in her 2013 TED talk. She defines single stories as the narrow-minded perspectives that exist when diverse representation is non-existent. Single stories fuel stereotypes.

I have to ask book banners: Have you actually read these books from cover to cover or are you reading the SparkNotes summary? What do people think quality education really is?

As a parent of two school-aged children, having knowledge averse individuals dictating what books my children could possibly access is a hard no for me. Black people lost the privilege of shielding their children from the travesties of the world long ago. We can’t shield them from what’s happening in the real world. But using literature to make sense of the complexities of police brutality, gender identity, and race provides a useful starting point. Responsible, educated teachers can spearhead balanced discussions in classrooms. Parents who value diversity and diverse perspectives in literature and support teacher efforts, make your voices heard at school board meetings.

In a world of diverse people, many stories matter.