By Sylvester Brown Jr.

Robert Norman Vickers Sr. remembered hardly being able to believe what he was seeing on television on July 12, 1999, as a group of 300 protestors descended the western ramp from Goodfellow Boulevard onto Interstate 70. The scene made Robert (known to family and friends as Bob) and his wife, Claire, at once proud and very uneasy.

Planned to perfection, volunteer drivers had positioned themselves in front of morning rush hour traffic on the three-lane highway. As if on cue, they slowed, then stopped, forcing cars in the rear to follow suit. That’s when the throng of protesters entered the highway. With protest signs and chants of “No Justice, No Peace,” they stopped, stood, and sat on the highway.

The Rev. Al Sharpton joined high-profile locals like Jim Buford, then director of the Urban League of Metropolitan St. Louis. They were accompanied by others of lesser notoriety but with shared outrage. At the time, the Missouri Department of Transportation had awarded just 3 percent of its highway construction contracts to minority firms. The protest took place on a section of highway that sliced through some of the poorest and blackest neighborhoods in the city.

Reporters captured it all, interviewing some of those arrested after the 45-minute shutdown. They identified attorney Eric Vickers as spokesman and key organizer. His parents had long known of Rick’s activism which started with a high school protest and was followed by a walkout at a fast food restaurant where he was manager. But this was on another level – a spectacle drawing world-wide attention, and one that could put him in harm’s way.

Sadly, Eric – who most people in the family called Ricky – died of pancreatic cancer in April 2018. His brother Steven passed away four months later in August 2018. His mother Claire died in 2012, as well as his older brother Bobby in 1992. And on Dec. 3, 2021, his father Bob, age 94, a profoundly influential educator and civic leader, and the patriarch of a family of vibrant, engaged citizens, died at home surrounded by his loved ones.

Bob’s complicated family history and his nearly century-long presence on both sides of the river in many ways captures how race has been lived in our region.

The only Black family in town

Bob died at his home on Dalkeith Lane in one of the 22 Copa Villa homes built in the early 1950s in University City. Like the journey that took him to that unique neighborhood, his past is complicated.

Thelma Robinson Vickers, Bob’s mother, was one of Alex and Callie (Woodson) Robinson’s 12 children. Thelma married Beverly Vickers while pregnant with her brother-in-law Tom Hardiman’s child, and Beverly was aware of that at the time of their marriage. While Beverly Vickers was never cruel to his stepson, he also never showed him any affection. So when Bob was a small boy, he went to live with and be raised by his maternal grandparents. Bob always spoke affectionately of the people who were his true parents, and cherished his time with them. Thelma went on to have four more children with Beverly: Dorothy, Duane, Caryl, and Jimmy – Bob’s siblings who grew up in the same town but were not raised in the same home.

Bob’s grandfather Alex was born in Virginia in either 1869 or 1872 (his daughter Vikki Deakin has found records that show both) and moved to Tazewell, Tenn., for a while before settling in Lerna, Ill., about 50 miles south of Champaign. The Robinsons were the first Black family in the town of 366 in 1927, the year Bob was born.

Alex had no formal education. He was an outdoorsman, craftsman and a blacksmith by trade. Alex made money shoeing horses, sharpening plowshares (for a $1.75 each) and hand-carving intricate stocks for shotguns, Bob recalled in a 2018 interview.

“Grandfather was always whittling something,” Bob said, pointing to a wooden walking stick with a baby’s foot carved on the end. It was a gift Alex gave him when he was a boy.

Although Alex could have easily passed for white, his ethnicity was well known in Lerna, so much so that the Klu Klux Klan attempted to run the family out of town. This was before Bob was born, but he relishes the story his grandfather shared with him.

“He had such a solid reputation in the town, that whites surrounded the house and put riflemen on a building across from the house. When the Klan showed up in their cars and trucks and tried to light a cross on his front lawn, a couple of white guys told them, ‘You S.O.B.’s can light that cross if you want to, but it’ll be the last thing you’ll ever light.’

“Well, they got back in their cars and left, and my folks never heard from the Klan again,” Bob chuckled.

Race was a different matter for Bob at school. “Being the only Black kid in school I got called ‘nigger’ or ‘eight ball’ a lot by opposing team members. My jersey number was ‘eight’ so I didn’t really get mad about it. But some of my team members got into it with those players who called me names.”

For Bob, whites who stood up for him overshadowed those who judged him by his skin color. He proudly recalled the times his basketball coach told racist restaurateurs, “’Well, if you won’t serve him, you won’t serve any of us,’” Bob said. He remembers the whole team walked out of those diners in silent protest.

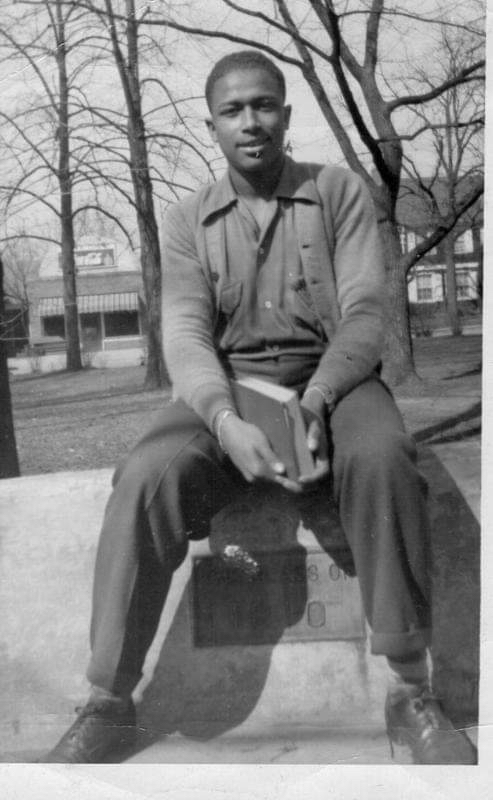

Cashing his ticket out

As a youth, Bob believed that education would be his path to a better life. He excelled in athletics and academics in high school. He was captain of the basketball team and president of his junior high and freshman classes at Lerna. There were only nine kids in his graduating class and Bob was the salutatorian. He believed race was the only reason he didn’t get the top honor. “I should have been valedictorian, but I lost by one-fourth of a point, they said,” he recalled, shaking his head. “But I didn’t believe them.”

When the valedictorian turned down the accompanying scholarship, it was awarded to Bob. He was the only student from his graduating class in 1945 who went to college. He enrolled at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston. Out of the 700 or so students at the university at the time, he recalls being one of only three African-Americans on campus.

His intent was to major in physics and chemistry, but a conversation on registration day with a couple of white students changed his mind. “They told me about the industrial arts field,” he said. “It intrigued me. So, on that very day, I changed my major and went into industrial arts.” Bob described Charleston as a “welcoming town.” He graduated in 1949 and remembered no noteworthy racial incidents.

Teaching in Venice

It was tough finding a teaching job after graduation, so Bob went to work at St. Louis Southwestern Union, a railroad company on the Missouri side of the Mississippi River.

In 1950, he got his first job as an educator, teaching industrial arts classes at Lincoln High School, established for Black students in 1909 in Venice, Ill. The town was named after Italy’s Venice because of its frequently flooded streets that were unprotected from the river. It was part of the heavily industrialized “tri-cities” area across from St. Louis which also included Granite City and Madison.

In the early 1900s, Venice was a modestly prosperous burg with about 5,000 residents, mostly white. Railroad tracks divided the city into north and south and Black and white. North Venice was dominated by African-Americans, many of them squatters living along the river.

“There were distinct boundaries where Black folk and white folk lived,” Bob said, recalling long-gone names like Pollock Town, Firework Station, Eagle Park Acres and Kerr Island, the last two located in Venice.

In 1940, 60 Black families on the water’s edge were forced off Kerr Island. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat explained how the evacuation of the shantytown was necessary in order to build the $10 million Venice Power plant (now part of AmerenUE) under the McKinley Bridge.

Beginning in the 1960s and continuing through modern times, Venice as well other East St. Louis neighborhoods progressively became almost entirely African American.

Life on the East Side

Bob moved in with his Aunt Esther in nearby East St. Louis in 1950. At the time, the city had a diverse populace with an economy powered by steel mills, aluminum factories, foundries, stock yards, power plants and meat-packing facilities. As in Venice, most Blacks settled along the riverfront, claiming a piece of land, building make-shift dwellings and calling them home.

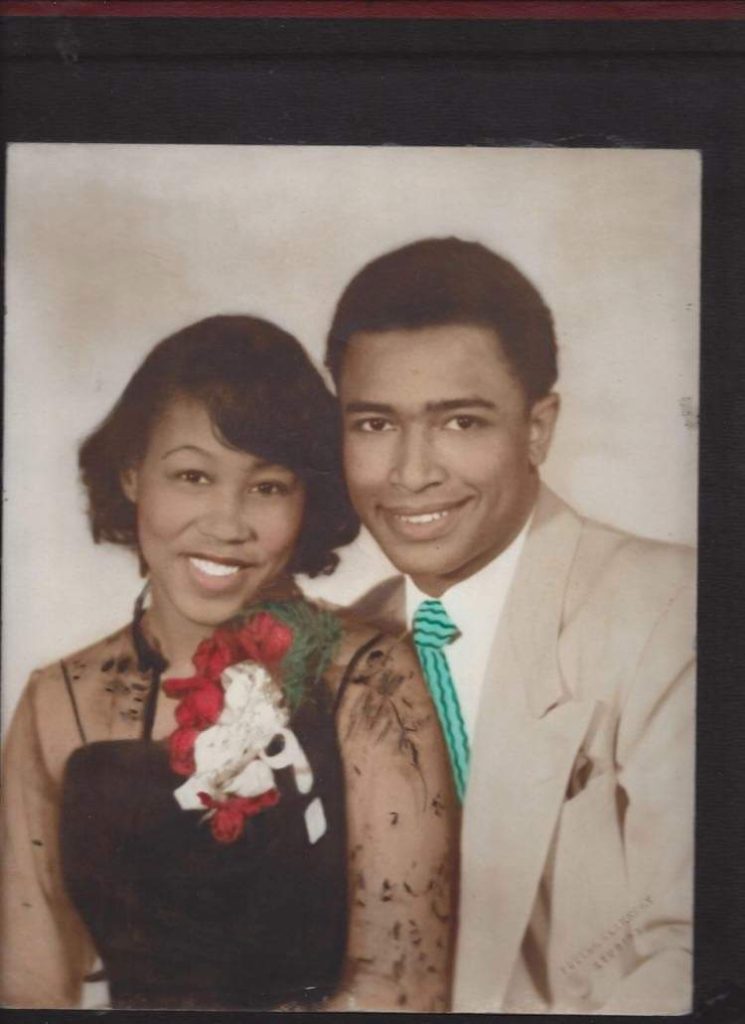

On Mother’s Day 1950, Bob was looking out Aunt Esther’s window when his gaze was drawn to a young woman walking across the street. Claire Lee Bush was the only child of Sam and Lillie (Pollard) Bush of Macon, Miss. Her parents sent Claire to East St. Louis to live with relatives, because as daughter Vikki would later recount: “She was a girl, she was smart, and there were no opportunities in Macon.”

Claire, who was born in 1932, had an independent streak that was evident as a schoolgirl, Vikki said. “Mom was a rabble-rouser in her own way.” In the 1940s and 1950s, when Claire attended school, the push was for girls to take home economics classes, so they’d grow up to be good homemakers. School administrators tried to move her mom in that direction, but Vikki said Claire insisted on taking history classes. “That’s why Bobby, Rick, and I loved history so much,” Vikki added, referring to her brothers.

Claire had just graduated from Lincoln High School in East St. Louis. She had broken up with her fiance, Paul, the high school quarterback the day before she met Bob.

Their courtship is part of the family lore that Vikki recounted.

“Daddy came up to her at a dance and told her, ‘If you wait for me, I’ll come back and dance with you.’ She did not wait for him. Then he made a date with my mother – but forgot that he had made a date with another girl for the same night. They were supposed to go to a baseball game. My father called and told my mother he couldn’t get tickets. But my mother knew the girl my father took out that night. So when my father showed up at her aunt’s house for their rescheduled date, my mother had her friend Mickey, who my mother knew was gay, be there on the porch with her. When my father asked who was that sitting with my mother, my mother said, ‘This is Mickey. He could get tickets to the game.’”

Their first date was memorable. “I took her to State’s Park (now Frank Holten State Park). She claims I tried to rape her,” Bob laughed. “I didn’t, but the next morning, I had all these scratches on my face. The students asked me what happened. I said, ‘Oh, my little cousin scratched me.’”

Vikki added later: “My mother said that my father acted like all girls from East St. Louis were ‘easy.’ She quickly disabused him of that notion.”

Rocky start aside, beginning in July 1950, Robert and Claire had an affectionate but Platonic relationship for several months, Bob remembered.

A few weeks after he started dating Claire, he got a call from a relative about the outcome of an earlier tryst with another young woman. “My aunt told me the girl was pregnant,” Bob recalled. Out-of-wedlock pregnancy was not only frowned on in the 1950s, it was scandalous. Bob’s boss, the principal at Lincoln High, found out about the pregnancy and insisted Bob “do the right thing” or lose his job. Though he had doubts that he was the baby’s father, Bob married the young woman in August 1950.

He told Claire everything and she matter-of-factly stated she “didn’t date married men.” Regardless, they still saw each other. Bob swore to Claire that he’d divorce the woman as soon as possible.

Bob’s suspicions were confirmed when his new wife had the baby, “full-term, five months after we were together intimately,” he said. Bob took his wife and new baby with him to visit family in Mattoon, Ill. at Christmas time. He left his wife and child there on New Year’s Eve and returned to East St. Louis alone to be with Claire.

After his wife came home, Bob said he wrote her a “nice long letter.” The letter laid out his concerns about the baby’s birth and the fragility of their marriage. He left the letter for her to read before he went to work. When he returned, Bob said, “She, the baby, and the letter were gone.” They divorced in March 1951. Bob married Claire in June. She was three months pregnant.

Raising a family

In the 1950s, Black babies in East St. Louis were delivered in the basement of St. Mary’s Hospital. It was a deplorable and unacceptable option for Claire. “I refused to have any child of mine delivered in that environment,” she told Elizabeth Vega, a Riverfront Times reporter, in 2001. “I would have rather delivered at home with a midwife in my own basement.”

Robert Jr was born in November 1951, and the two children who followed were delivered at People’s Hospital, at 2221 Locust Street, the healthcare facility dedicated to serving Blacks in St. Louis.

When Claire moved in with Bob, he was staying on the bottom floor of a two-story house on Missouri Avenue. They soon moved to an apartment on South 17th Street. Ricky (Eric on his birth certificate) was born in 1953. In 1955, the family rented a two-bedroom brick home at 1810 Piggott Avenue owned by Bob’s relatives. All three dwellings were in southwest East St. Louis. The Vickers’ third son, Steve, was born on Piggott Avenue in 1955. It was the house where the family spent the rest of their time in East St. Louis.

The RFT profile described the area surrounding Piggott Avenue as “a segregated urban neighborhood, rowdy and alive with children.” The Vickers family owned the first color television on the block, which made their home a magnet for the kids’ friends. When programs like The Green Hornet were on, “there would literally be 15 or 20 kids watching,” Ricky said in 2001.

Although there were plenty of kids in the neighborhood, few fathers lived in their homes, Bob said. He became a surrogate father to many of them, playing sandlot baseball and other games with the children. “I can honestly say, it was the happiest time of our lives,” he would recall.

Plenty of work

After Ricky’s birth, Bob took on a side job selling life insurance.

“I sold what was called industrial insurance policies,” he said. “I didn’t have a car back then, so I mainly focused on the colored side of town. Many of the doors I knocked on were the homes of the kids I was teaching.”

The “colored side of town” served Bob well: “During that time, people had lots of work. Claire and I palled around with people who worked at Monsanto, the glass or steel companies, or other factories.”

Claire went to work in 1957. She had taken classes at the now-defunct Mildred Louise Business College on 3116 Bond Avenue in East St. Louis. With certifications in typing and shorthand, she got a job with the federal government at one of its buildings on 12th and Spruce streets in downtown St. Louis. By 1963, Bob had become principal of Lincoln High in Venice.

He described the schools in East St. Louis as subpar. The elder boys attended Dunbar Elementary School near their home on Piggott. Their parents did not want them to go to the declining Hughes Quinn Junior High, so they used a friend’s address to send Bobby and Ricky to Rock Junior High. It was still a predominantly white junior high school then, but Bob said “it was rapidly changing, with more Black teachers and students coming in.”

Bob said he and Claire had stern rules regarding their sons’ education.

“We stayed on them, especially Claire. She would tell them they had the ability to do well and ‘Cs’ were just not gonna work. So, they were both average or above average students.”

Time to leave

Although East St. Louis had won the prestigious “All American City” award from Look magazine in 1960, the economic landscape was collapsing. Outdated factories were closing rapidly. The construction of new freeways disrupted neighborhoods and broke community links. At the same time, those highways provided an easy escape for workers to commute back and forth to suburban homes and newer housing outside the city limits. “White flight” was in full effect across America and East St. Louis was no exception.

By 1960, Black unemployment in East St. Louis was at a staggering 30 percent, three times the rate for whites. Between 1950 and 1970, 50 percent of the industrial jobs vanished. As jobs and wealthier whites left, street gangs, political corruption, poverty and empty buildings surfaced.

Bob and Claire decided it was time to leave. “The kids didn’t really want to move,” he recalled. The city and the friends they’d made were all they knew. But their parents had made up their minds. “I couldn’t save the whole neighborhood,” Claire recalled in the RFT interview. “I had to make sure my own were going to succeed.”

They initially thought they’d stay east of the river and move to the nearby Belleville area but, Claire said, because they were Black, no real estate agent would show them houses there. Claire had read about University City’s “open housing” movement aimed at recruiting Blacks into the area. The city was at the forefront in battling “white flight” while welcoming middle-class Black families.

A June 10, 1964, Post-Dispatch article summed up the city’s achievements: “University City was the first county municipality to have a public accommodations law, the first to have a general fair employment law and the first to create a human rights commission. Now it has become the first to adopt a strong policy for equal rights in housing. For this University City stands as a model in human rights achievement.”

University City may have been lauded for its efforts to integrate Blacks into its neighborhoods, but Claire wasn’t experiencing the benefits. She had grown weary of agents’ insistence that her family move into “the Black section” of town, north of Olive Boulevard. By this time, Bob was assistant superintendent of the Venice School District and Claire worked for the federal government. They could afford to live in any University City neighborhood.

Fed up, Claire dropped her agent and began searching for a home in U. City on her own. She found one on Groby Road, but Bob thought it was too expensive. Then they settled on one nearby on Dalkeith Lane with three bedrooms and 1.5 bathrooms, though in Claire’s mind it was too small for their growing family. They bought it in 1967 becoming the first Black family on the block.

Seeds of activism

Perhaps it was during the move onto Dalkeith Lane that the activist urge took root in Eric. In the RFT interview, he spoke of his father’s reaction to a racist neighbor who tossed a log through their window and smeared black paint on the side of the house. He recalled the image of his 14-year-old self, surrounded by moving boxes, standing in the dark house next to his father. With his grandfather’s shotgun by his side, Bob peered through the glass window, anticipating another attack of vandalism. “I don’t know why, but I wasn’t scared,” Eric said. “I knew, whatever happened, my father would make sure we would be OK.”

Everything worked out. Other Dalkeith Lane neighbors welcomed the family and let them know that they did not feel the same way that one racist neighbor with an agenda felt. Bobby and Eric enrolled in University City High School while Steve went to Brittany Junior High. The teens made new friends and did well in school.

When an assassin’s bullet ended the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, the news leveled the Vickers family. Elizabeth Vega shared the family’s recollections in her 2001 Riverfront Times profile. Hearing the news on the radio, Bob left his car in the driveway and went inside to tell Claire. With tears in her eyes, she told her sons of the tragedy. Bobby, the eldest, went to his room and closed the door, “shutting the world out.” Steve, the youngest, wept openly. Eric, however, was consumed with rage, Vega wrote. He “walked out his front door and kept going.” All his heroes, John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X and, now, King had been slain mid-mission.

“The death of King and Malcom X started the pot boiling,” Eric told Vega.

Five miles and two hours later, Eric returned home, she wrote, “quiet and introspective. But deep inside him, a fire had started to burn.”

That fire ignited in 1970, the same year his baby sister, Vikki, was born.

By that year, 2,287 Black families had moved into U. City, representing 18% of its population. The new Black residents had more school-age children than whites in the area. Blacks made up 40 percent of the public schools’ population with percentages rising, according to the UMSL study.

Since its inception, University City took pride in its vibrant, accessible neighborhoods and its public schools. Realizing that an excellent school district is an essential part of any first-class community, public schools were always a high priority on city leaders’ agendas. The influx of so many Black children in such a short time span, however, challenged school administrators’ ability to quickly adapt.

Students stage strike

At 7 a.m. on March 17, 1970, Black and white students, including Eric, initiated a strike. Some of the fist-waving students sported Black berets and army fatigues like the Black Panthers. The strikers blocked the school’s doors. Their demands, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, included, “daytime Black studies programs for all students, Black holidays to be treated by the administration in the same way as Jewish holidays, more (Black-oriented) books for the school’s library, intensified efforts to recruit Black teachers and more frequent use of Blacks as guest speakers at the school.”

Meetings were held with parents, other residents and school officials. Most of the students’ demands were met. Within days the district hired a Black teacher and a Black counselor. African-American literature was added to the school’s library. That brought an end to the protest. But Eric’s passion for civil disobedience, activated by the strike, was just beginning.

After the high school demonstration, Claire advised her son: “Don’t ever back a man in the corner unless you give him a way out. He will have no choice but to come after you.”

He took his mom’s admonishment to heart, but fighting “the system,” like his heroes Malcolm and Martin did, had an undeniable appeal.

And baby makes four

Bob wasn’t pleased when Claire gave him the news that she was expecting another child. He was 43, she was 38. By then, they were financially stable. Bobby had left the house and Eric was attending community college. Steve, the youngest boy, was about to graduate from junior high school. The couple had been talking about Bob’s retirement and doing the things they couldn’t while raising the boys.

Even though he was upset, Claire “was happy as could be,” Bob said. After a miscarriage three years prior, Claire had been told by her doctor that she would never have any more children. This child became her “miracle baby,” as she called her daughter often later. Convinced they could only have boys, he, too, shared Claire’s excitement when she gave birth to their daughter, Vikki Jan “VJ” Vickers, on November 30, 1970.

Steve enviously called his baby sister “Princess” because his father doted on her. Bob admitted that he’d light up whenever he was with his baby girl. “She was a joy, self-motivated and independent at an early age,” he said.

Family ordeal

By 1973, Bob had been promoted to superintendent of the Venice School District. One day at work, he got a call from Steve that he needed to come home because something was wrong with Claire. He found her in bed when he got home. Bob noticed her mouth seemed to be twisted in an unusual way.

Doctors at Jewish Hospital confirmed Bob’s suspicions. It was a stroke. Although Claire tried to dissuade him, Bob said he’d visit the hospital before and after work every day. Claire’s mother came from Mississippi to help take care of the kids while Claire recuperated.

Although Claire was partially paralyzed and walked with a cane, the stroke didn’t affect her speech, mental capacities or mobility, Bob said.

“She never let it stop her. She drove the car, took Vikki to school every morning, and did whatever it was she needed to do around the house.”

His wife also clung to the notion of recuperating. “She would always say, ‘When I get better,’ we’ll do so-and-so,” Bob recalled. “Eventually, though, I think she came to the conclusion that she wasn’t going to get better.”

Vikki never saw that side of her mother. “The Mom I knew was always disabled but that was my normal,” she said. “She adjusted the best way she could.”

Life with Dad and Mom

When Vikki entered kindergarten, University City’s public schools “were thoroughly integrated,” according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

From kindergarten through fifth grade, Vikki attended McKnight, one of four elementary schools in U. City, with an 11% Black student population in 1970. McKnight merged with Jackson Park Elementary the year after she left and went to Brittany Woods. Even at a young age, Vikki noticed and appreciated the school’s growing diverse population. “We had a Russian invasion when I was in fourth grade. There were Russian kids, Black kids, white and Asian kids. It was very U. City,” she laughed.

Many kids within that eclectic dynamic were also Vikki’s neighborhood friends. “I knew all the kids and all the teachers,” she said. “I remember the ice cream socials and amazing teachers. I loved McKnight. I just have the best memories.”

Her elementary school memories are mixed with her life at home. Vikki remembered especially the wonderful bond she had with her dad after Claire’s stroke. “I loved my mother fiercely — but I’m a true daddy’s girl. I was his running buddy. We did everything together,” Vikki said. “I’d always go with him to get groceries and I’d take my giant Raggedy Andy doll with me. Andy sat in the cart and I’d walk the store with Daddy. He’d teach me about bargains and how stores could be deceptive about prices.”

Vikki was also Bob’s companion at the Venice High school basketball games. She remembers faculty and team players whispering “that’s Mr. Vickers’ daughter.” She recalled the day her Daddy told her he had a surprise for her. They skipped school, got in his car and drove downtown to see Blackstone the Magician. “It was so much fun,” she said.

Vikki said she sometimes felt like her brothers were more like uncles. After all, there was a 15-year gap between her birth and that of Steve, the youngest brother. Steve graduated high school and joined the Navy before Vikki began kindergarten. The eldest, Bobby, had left the house and Eric, although still living at home, was attending Forest Park Community College.

She remembers how her brothers looked out for her. Before she had her hair relaxed, Steve and her Dad worked on her afro before going to work and school. She was closest to Steve, but it was Ricky, who helped “broaden my horizons,” she said.

Ricky was the one who spent long, patient hours teaching her to ride her two-wheeler. He enjoyed “teaching me things,” Vikki said.

“When I was like four or five, he showed me what an octagon, pentagon, and a hexagon was and how many sides each one had,” she said. “I remember him teaching me what the colors of the red, black and green Black Nationalist flag meant. He liked to challenge me.”

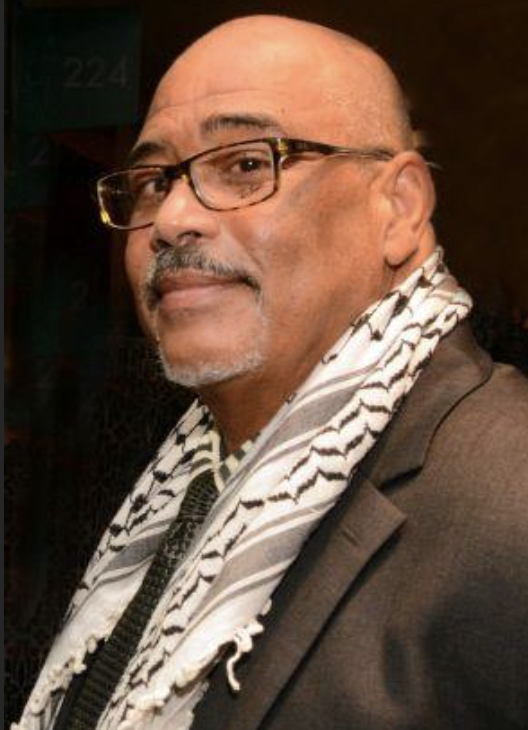

Leading the charge

Then came the summer day in 1999 when Eric drew the attention of the region and the nation – the highway shutdown.

Eric had been in the news for his activism back in 1990 when he represented minority contractors in a federal lawsuit against the city of St. Louis. That action led to the “25/5” consent decree and eventually an executive order mandating that, of all St. Louis contracts, 25 percent must be awarded to minority businesses and 5 percent to female-owned businesses. In 1996, Eric chartered a TWA jet and flew more than 100 people, some of them homeless, to New York to protest discriminatory banking practices. That action eventually led to a $100 million minority commitment from bankers.

He had also gained some notoriety across the river when he was serving as attorney for East St. Louis and Carl Officer, its controversial mayor and Eric’s childhood friend. During a case concerning overflowing city sewers, a judge sent both Eric and the mayor to the St. Clair County jail for contempt of court because they had missed a court date.

After the I-70 shutdown, however, Eric became the topic of national news, praise, and scorn. The demonstration was a dramatic departure from previous nonviolent protests in St. Louis. It also sparked change for the better. The construction training program negotiated after the protest has produced more than 1,000 graduates and ushered hundreds of young minorities into the construction field.

Still, on that day in 1999, watching the news, Bob had a hard time reconciling what he was seeing. He couldn’t believe that his second-born son had pulled off such a coup.

Vikki heard about the shutdown while she was in graduate school at the University of Missouri. She got the details from phone calls home with her parents. “I remember them talking about raising bail money,” she said.

The senior Vickers weren’t exactly enthusiastic about the highway shutdown or, to be honest, most of Eric’s protest activities. “I remember Dad asking, what was the point (of the protest)?” Vikki said. “But there was no point in being against him, Ricky was gonna do what he was gonna do.”

In the 2001 interview with the Riverfront Times, Claire admitted that she worried about her son’s activism:

“He is fighting windmills like Don Quixote and keeps taking on the system,” she said. “He wants to move the whole world instead of trying to move it one piece at a time. He cares about things so deeply that he hurts when he can’t get things accomplished. I can see it in his eyes. He doesn’t have to say a word.”

Baby sister moves on

Meanwhile, Vikki was immersed in academia. Her parents had always preached that education was critical, and that college must be a part of her future. They were also realists who stressed financial responsibility with their only daughter.

“I remember telling my parents when I was 11 that I wanted to go to Harvard. Daddy said, ‘OK, but how are you gonna pay for it?’ I said, ‘I’ll get a scholarship,’ and he replied, ‘that would be fine.’”

After graduating from University City High with scholarship in hand, Vikki enrolled at the University of Missouri in Columbia. She spent 13 years in Columbia, earning her bachelor’s degree (1993), master’s (1996) and her doctorate in history in 2002.

After graduation, Vikki accepted a temporary assistant professor of history position at Middle Tennessee State University. She had an apartment on the Stones River in Murfreesboro, Tenn., a town known for its affinity to the Civil War (because of the Stones River Battle that took place there) particularly the Confederate side. “Tennessee is beautiful but there’s way too many Confederate flags. It was hard,” Vikki said. “Teaching history can be a minefield.”

The diversity she found in Tennessee, however, was refreshing. “The school was a good 45 percent Black, which I loved. It was the first time I had classrooms that were almost half African American.”

In 2005, Vikki moved to Utah to teach at Weber State University, where she still lives and works today as a full professor. Utah, she says, is the total opposite of Tennessee. “It is the whitest place on earth,” she said. “There’s been a huge growth in the Latino population, which the state isn’t handling very well, but I’m enjoying it.”

Loss of the matriarch

A year before Erica (Eric’s daughter) married, she received terrible news from home. Claire, her grandmother, had had another stroke. Bob had already retired as superintendent of the Venice School District in 1987, but he was out the morning Claire got sick. It was the day of their 55th wedding anniversary. She was home with their son, Steve. Robert Jr. (Bobby) had passed away in 1992 from complications related to diabetes. Bobby had married twice and claimed nine kids from the unions. One of his children, Kwira, was also at the house.

Claire had tried to get out of bed but fell to the floor. Kwira yelled for her Uncle Steve, who was a registered nurse at the time. “Steve knew right away she was having another stroke,” Bob recalled.

Claire was rushed to a hospital, where doctors told the family she had a blood clot in her brain.

Bob thought it odd that doctors never operated but he trusted their decision.

Vikki said she was glad to have returned to the family home when her mother was released from the rehab center. “She was just so helpless, and Daddy was so overwhelmed,” she said. “She was on a feeding tube then and bedridden. But we managed. I helped Daddy establish a routine with her, getting her pills together, and helping with her feeding schedule.”

Her father was amazing during the following three years of daily caretaking, she said. “He had help of course, but he never wavered,” Vikki said. “He never considered anything but being there and taking care of her.”

One night in 2012, as Bob would recall in our interview, he and Claire were lying in bed watching television. Earlier that day, she had complained about stomach pains but insisted she didn’t need to go to the hospital. After a few moments of unusual silence, Bob said he looked over at his wife: “Her eyes were glazed over.”

An ambulance was called. Paramedics told the family Claire’s heart had stopped but they revived her before she arrived at the hospital. Doctors told the family her heart just was not strong enough to sustain life. In Bob’s mind, though, Claire had died in their bed, by his side.

Death of Michael Brown

Just as the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 moved the first and second generations of Vickers, Erica and Ahmad – Eric’s daughter and grandson – had a similarly disturbing reaction 46 years later.

The killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown on August 9, 2014 by a Ferguson policeman was a hot topic at Ahmad’s school. Fellow students, he recalled, “seemed on edge, overly sensitive and edgy.” It was hard for Ahmad to find the right perspective. He understood his peers’ criticism and condemnation of the ensuing riots, but he couldn’t quite wrap his head around police in military gear. At 5’8 and 270 lbs, he also couldn’t escape the physical similarities he shared with Brown. “He could have been me,” Ahmad said.

The similarity lent to his mother’s extra levels of paranoia.

Brown’s death was a culmination of all things Erica feared related to her son growing up in a majority white environment where “big and Black” often equates to “suspect and dangerous.”

She had already warned her son to be careful in choosing the people he hung out with or places he frequented. She’d given him the protocol if he was ever stopped or detained by the police: “Be compliant, keep your hands in plain sight and call me or your grandfather, immediately.”

That advice seemed even more critical after Mike Brown’s death.

“I know you are friends with them (white kids), and you love them…and there’s nothing wrong with that,” Erica told Ahmad. “But remember, your skin color makes you different. People will always see your Black skin before they see you. That’s just reality.”

Still connected to U. City

Now 40, Erica Vickers Cage continues to live in Shiloh, Illinois close to where her husband, Warren, works. Ahmad is now 20, and Erica’s other children, Felecia and Layla attend Shiloh Middle School, which is 64 percent white, 21 percent Black and the rest other minorities. Erica says nearly all of the girls’ friends are white.

“I’ve always grown up around diversity,” she said. “It’s something that I embrace and something that a lot of people don’t understand. It’s all you know and all you want.”

Over the last couple of years, Erica had been a caregiver for Bob, along with her cousin, Kwira. Sometimes when she brought her girls to University City where she was raised, she gets pangs that they are missing out on the rich experience that she had growing up.

“They’ll say, ‘Who are those people walking with the long beards?’ And I’m like those are Jewish people and they’re going to their church. It’s called a synagogue. They’re missing out being exposed to different ethnicities, cultures, and religions on a daily basis. That’s why I say I would love to move back to U. City. I hate that my children haven’t inherited that cultural experience.”

Erica’s parents ensured she had a great relationship with all of her grandparents; and she did the same for her children. Erica and her grandpa went to dinner several times a year. “Grandpa exposed me to fine dining. I tease my husband all the time, my palate is more sophisticated because of Grandpa. Grandpa was a man of principle, integrity, and strength. Nobody could ever question what Grandpa was thinking because he was straight forward and intentional with every decision he made.”

You can view the celebration of life for Robert Norman Vickers Sr. by clicking on this link.