Facing seven doubleheaders in September, the Cardinals can find inspiration in the Mathews-Dickey Knights, who won five games in a single day to win a championship

By Richard H. Weiss

Special to the Riverfront Times (Published Sept. 2, 2020)

With at least seven doubleheaders facing them over a stretch of three weeks in September, the Cardinals face a daunting task if they hope to make it to a World Series title in this pandemic season. May they find inspiration in another hometown team that had to sweep a quintupleheader to bring home a semi-pro championship.

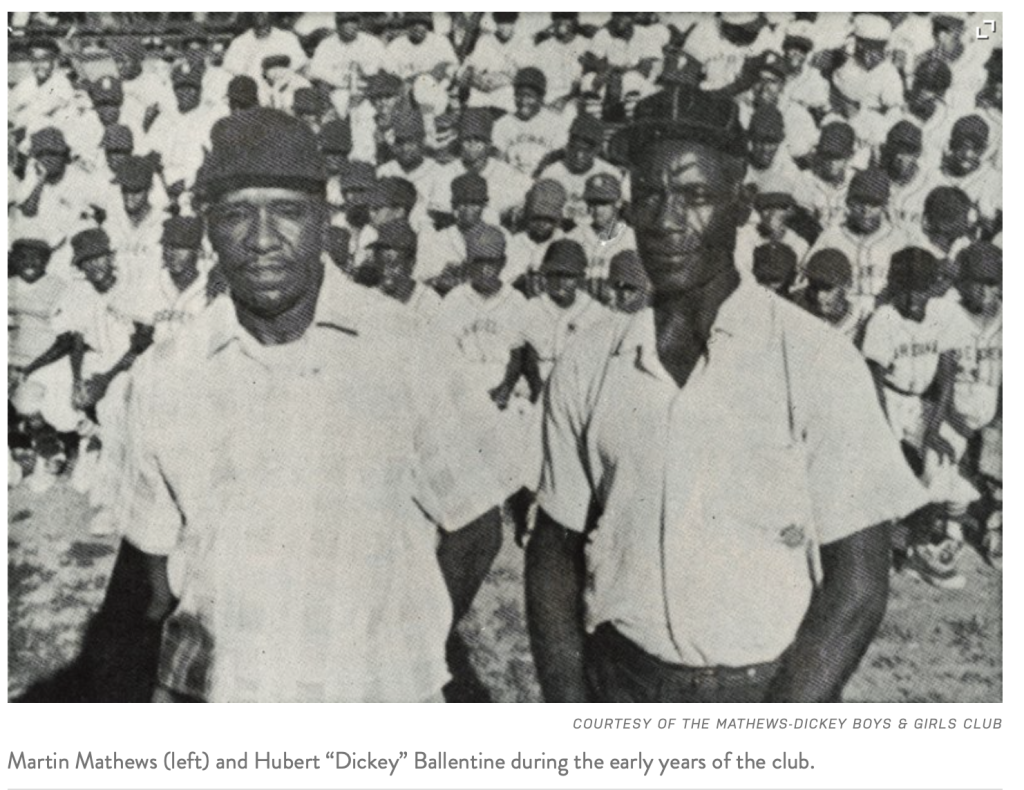

That would be the Knights from the iconic Mathews-Dickey Boys’ Club. At 1 p.m. July 4, 1977, the Knights took the field at Fairgrounds Park Field #1 under a cloudless sky. At the time, they had no idea they would be playing ball until the early morning of. July 5. A day earlier, the Knights had lost the first game of a double-elimination tournament that included seventeen teams. To get a shot at the championship, they would have to win every game they played the following day or go home.

More than bragging rights were at stake. The winners would leave with $1,000 cash money that would be handed over in a paper sack. The Knights very much needed the dough, as the team was in hock to Johnny Mac’s Sporting Goods for their uniforms and equipment.

Not many outsiders figured the Knights had a shot. Certainly not the loudmouth fan who had a son playing for the Chicago Pirates. He went around placing hundreds of dollars in bets on the Pirates vs. the Knights.

But these young men were made of much sterner stuff than anyone could possibly know.

A case in point: Tom “Big Sully” Sullivan, then age 22, among the youngest on the field that day.

Today, Sullivan is Mathews-Dickey’s interim president and CEO. He is also its longest serving staff member, having started in 1973. He was born in Pocahontas, Mississippi, about ten miles outside Jackson, the state capital. His father died when he was seven, and the family moved to St. Louis’ west side, to a home on Cabanne Street near Kingshighway. His mother Velma worked as a domestic by day, as well as at a dry-cleaning business, and then served as a custodian at night to support her five children.

To help out, Tommy, as Velma called him, began taking on jobs. By age thirteen, he served as a security guard for a furniture store. He sold newspapers out of a cart, and, while dodging pimps and pushers on the way, he would show up at 4:30 a.m. to work at a Kentucky Fried Chicken store, where the owner had entrusted him with the keys. When he got his driver’s license, Sullivan continued working but also took his mother to her jobs so that she wouldn’t have to ride the bus. Along with all that, he attended Sumner High and excelled at baseball and football. He graduated in Sumner’s centennial class in 1975.

Sullivan went on to Saint Louis University, where he became known as Big Sully. There he set twelve offensive records as a Billiken — for home runs, stolen bases and walks, among others. He entertained an offer from the Pittsburgh Pirates, which was flattering but not substantial enough for him to give up his scholarship at SLU.

Sullivan had met Martin Luther Mathews, cofounder of the club with Hubert “Dickey” Ballentine, while he was in high school. The Mathews-Dickey Boys’ Club on Shreve and Natural Bridge became “my home away from home,” he recalled. He earned his first club paycheck through the Earn and Learn Program, where he became one of the commissioners who organized the games. There he met such men as William Ballard, Eugene Crymes, Frank Grice, Eugene Miller and Robert Trice. “They walked straight. Talked straight. They showed a lot of concern, and you wanted to be like them,” Sullivan says. “It gave me the idea that this was how you could be respected. I knew what I wanted to be, and it was something good.”

When Sullivan graduated from SLU, “Mr. Mathews” (everyone calls him that) introduced Sullivan to a top executive at Anheuser-Busch. On Mathews’ say-so and with his stellar performance at SLU, Sullivan got an offer to join A-B’s marketing department.

But he turned it down. “Number one, I didn’t drink beer. How could I tell anyone it tasted good?” Sullivan says. “Number two, I hadn’t paid back what I had gotten from the club.” Instead, he told Mathews that he wanted to work for Mathews-Dickey.

On the field and on the bench with Sullivan that day in 1977 were some old-timers, relatively speaking. These were men, a decade or more older than him, whose pedigree went all the way back to the founding of the club. They included brothers Barry and Herman Shelton, who played third base and right field respectively; first baseman Garland Goodwin; second baseman John May; catchers Curtis Edwards and Rodney Epps; pitchers John Bernard, Billy Westbrooks and Clarence Deloch; manager Osbie Savage; and coach Frank Robinson. There were 21 men who participated that day. Thirteen would later be inducted into the St. Louis Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame.

The old-timers were the kids who got going with baseball in the late 1950s. They used to gather on Mathews’ front porch in the Ville and ask him to come out and play. Mathews, a former semi-pro player, was supporting a wife and five daughters, and working a day job. But somehow he found the time, taking them to Public School Stadium or Handy Park and hitting fungoes ’til it got too dark.

One afternoon around that time, Raymond Turner heard about one of the practices. He hopped on his bike with his fielder’s glove and catcher’s mitt on either handlebar and a bat balanced between them. “As soon as I rode up, I knew I was on the team,” Turner laughs during an interview. That’s because Turner had some equipment. A lot of the boys didn’t.

After practice, as Turner recalled, the boys gathered around Mathews and wanted to know if they were ever going to get some uniforms that would make them look as good as the white teams they were going to play.

“If you were on a team, you had to have a uniform,” Turner recalls. “That was a big thing.”

The kids would beseech their coach and mentor: “Please, Mr. Mathews, can we get uniforms? We’ll even wear used ones.” Mathews scratched his head. “Even then, just thirteen years old, I could tell he had no idea how he was going to come up with those uniforms,” Turner says.

But that’s not what Mathews said. “Of course you’re going to get uniforms,” he told the boys. “And they’re going to be new.”

Well, says Turner, “when we played our first game, we not only had new uniforms with blue caps, we had new bats and balls. I don’t know how he pulled it off, but he did.”

Turner, the Sheltons and Curtis Edwards came from two-parent families. But their dads worked hard, sometimes at two jobs, and couldn’t always spend time with them. Mathews filled a void. And the dads appreciated it.

When they could, they would turn out to help coach or they would fire up their grills on street corners to barbecue meats that their sons would hawk to passersby. This in large measure was how Mathews got the dough to pay for the bats, balls, gloves and uniforms.

Edwards got a catcher’s mitt. His dad worked with a forklift at F. Burkart Manufacturing Company, where he got to know Mathews, who was a supervisor. Edwards’ mom worked a mop and a broom overnight at a couple of office buildings on the west side of town, returning home in the early morning to get her kids ready for school. Edwards attended Hadley Tech. In the spring, Edwards played for Hadley Tech, and in the summer for Mathews-Dickey.

He was a five-tool ballplayer, meaning he could run, throw, field and hit for average and power, Mathews remembers. “One of the best ever to play the game.” And he did so well into adulthood as Mathews-Dickey fielded an elite semi-pro team that would become the Knights.

It would be Edwards combining with first baseman Garland Goodwin that would pull off a pivotal play in the fourth game on July 4, 1977, that would send the Knights on to the championship game and the title late that night.

But let’s start in the morning, when Big Sully awoke and put on his uniform facing long odds and an uncommonly hot day. The mercury would soon bubble up to 95.

He woke up kind of pissed. The Knights were on the brink of elimination because they had lost to the Chicago Pirates the day before — and they “couldn’t carry our shoestrings,” he says.

The Knights had power and speed up and down the lineup. But the Pirates could “slap leather,” he recalls. In their first encounter, the Pirates found their way out of jams with a couple of double plays and even a triple play.

Still, Sullivan says, he and his teammates weren’t discouraged. “We knew to just take it one game at a time.”

Starting at 1 p.m. that day, Sullivan wound up playing every single inning, a total of 39 (three seven-inning tilts, with the last two going nine).

Not one of the Knights wilted, but some of the older players had to come and go because they had jobs or family responsibilities. Families provided provisions for the players. Robinson remembers hauling large coolers of ice in his Buick, and there was fresh fruit to keep the players going.

Asked if he paced himself, Sullivan says, not all that much. In fact, he may have made it tougher on himself by wearing “woolly sleeves” because that’s just how he liked to suit up. “My theory was that the sweat turns to water that keeps me cool.”

If any concession was made to the elements, it came ahead of or at the end of an inning. “We were taught to sprint on and off the field,” he says. As the day wore on, “I might have walked out to left field.”

Maybe that little bit of energy conservation had something to do with a catch Big Sully made in the late innings of one of the games — he doesn’t remember which — when a batter smoked a pitch in his direction. Sullivan knew it was going to be over his head, so he turned his back and ran as fast as he could to the spot where he figured the ball might fall. When he got there, he spun around, stuck out his glove and captured it to end the inning.

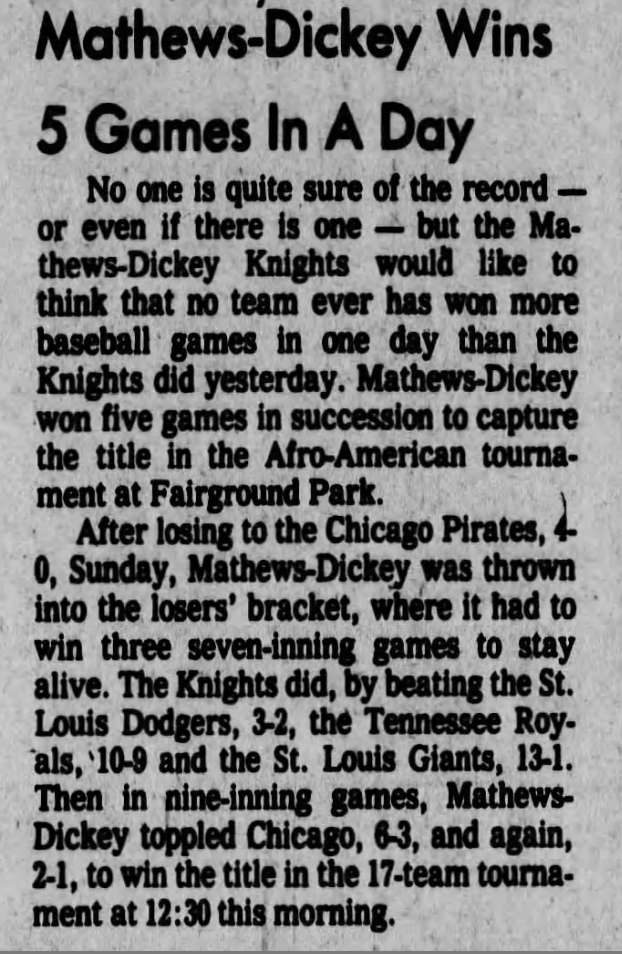

The Knights would need more heroics than that. They had defeated the St. Louis Dodgers 3-2 earlier in the day, then the Tennessee Royals 10-9 and the St. Louis Giants 13-1. To win the championship, they would have to beat the Pirates twice at night under the lights.

In the fourth game, the bases were jammed in the ninth inning with the tying run on first. Goodwin noticed that the Pirates runner was taking a substantial lead off of first. In that moment, Goodwin was playing well off the base to prevent a hit from getting through the infield. But he had an idea. What if he snuck behind the runner and took a snap throw from Edwards? But how was he going to get Edwards’ attention to make the play without tipping off the runner?

Fortunately, the two had been playing together for quite a while. And whenever Goodwin wanted to get Edwards’ attention, he would say a word that meant nothing to anyone but Edwards.

“WALTHAW.”

It happened to be Edwards’ middle name, one the kids had teased him about ever since he could remember.

After Goodwin got Edwards’ attention with the word, the throw came down after the next pitch. Game over. The denouement came so suddenly and so late that the 75 or so fans still at the game were stunned. They had hardly known what happened until they saw the umpires walking off the field. The Knights took that game 6-3, then won the final game 2-1, finishing up around 2:30 a.m.

Sullivan remembers taking some pleasure in watching the Pirates player’s dad pay off his bets. But Coach Robinson had his eyes on the prize. He headed over to grab that sack of title cash so that the team could make good on its debts. The cash was handed over in singles, fives, tens and twenties so loose and heavy that Robinson had to prevail upon someone to provide a paper sack to keep it safe and secure.

The five games won in a single day made the newspapers and are memorialized in a plaque that hangs at Mathews-Dickey today.

It was quite an accomplishment. But the more significant victories lay in the lives led away from the diamond by members of that team. Bernard, Goodwin, and Edwards launched into successful careers as teachers. Bernard would go on to develop an afterschool program with Mathews-Dickey for children at Scullin School in the late 1990s. Edwards taught physical education at a variety of public schools and coached football and baseball as well, while also working with the boys at Mathews-Dickey.

Goodwin, a Vietnam vet, taught at both of his alma maters, Blewett Middle School and Vashon, as well as O’Fallon Tech, Beaumont High and Clyde C. Miller Career Academy. He served as principal at Sumner High School. Goodwin retired in 2005 and passed away in July 2016.

Barry Shelton earned an undergraduate degree from the University of Missouri-St. Louis and also an MBA, and would spend his entire career at McDonnell Douglas, retiring as a senior project manager. He also served on the Mathews-Dickey Board in the 1970s and ’80s.

Robinson, a longtime board member for the club, attended Hampton Institute in Virginia (now Hampton University), studying architectural engineering and later transferring to Washington University, where he earned a degree in electrical engineering. He also holds several advanced engineering degrees from Washington University and has worked over the years for a wide array of blue-chip companies, including Missouri Pacific, Olin Corporation, Ralston Purina, McDonnell Douglas, IBM, CRD Campbell, city of St. Louis, Kwame Building Group, URS Corp. and AECOM. So when the sun is burning hot on one of those doubleheader days, when the sweat forms on MLB brows, when the bats feel heavy in their hands, the Cardinals might remember the Knights and the day they swept a quintupleheader.

Readers can honor this accomplishment and many others by taking part in the 60th anniversary celebration of the Mathews-Dickey Boys’ & Girls’ Club. It will be held virtually at 6 p.m. October 16. The event will feature a special presentation by Mathews-Dickey youth, alumni testimonials, music, and a special appearance by actor and native St. Louisan Sterling K. Brown, who once tutored at the club.

Register here for the event.

Richard H. Weiss is founder and executive editor of Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a non-profit racial equity storytelling project. He is the author of I Trust You With My Life: The story of Martin Luther Mathews and the many lives he transformed with cofounder Hubert “Dickey” Ballentine at the Mathews-Dickey Boys’ & Girls’ Club.