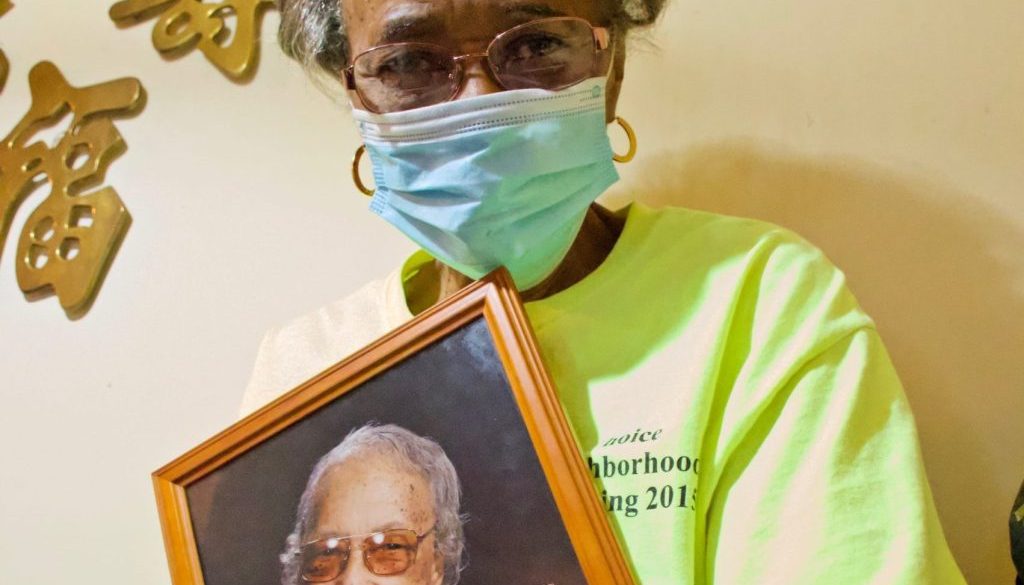

“I’m living. Some people are in worse shape than me,” says Valerie Nichols

This story originally appeared in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. Additional support provided by the Buckingham Strategic Wealth Pillar Grant Program and the St. Louis Press Club.

By Stu Durando

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

in cooperation with Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

Photos by Wiley Price/St. Louis American

Carrying a bag with a pair of pants, three tops, a pair of sneakers and a nightgown, Valerie Nichols left her home for Grand Manor Nursing and Rehabilitation Center not sure what she would find.

She had last seen her mother on March 1. She didn’t know when she would see or talk with her again after this Mother’s Day visit.

Nichols took a seat inside the front door; another door separated her and 90-year-old Willie Mae Nichols. The next 20 minutes made for a fleeting visit and allowed for an assessment of her mom’s condition, a few months after she was moved from her home to receive care for dementia.

As Willie Mae Nichols opened a card, her daughter paid close attention.

“I heard her read from the card. She read the whole thing,” Valerie Nichols said. “They say she doesn’t have nothing. She looked good on Mother’s Day — her color and everything. I do miss talking to her.”

Visits are not as easy as they were before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the St. Louis area. Restrictions on movement, as well as guidelines for avoiding the coronavirus, have largely kept Nichols in her apartment in the Preservation Square housing development, where she has lived since 1996.

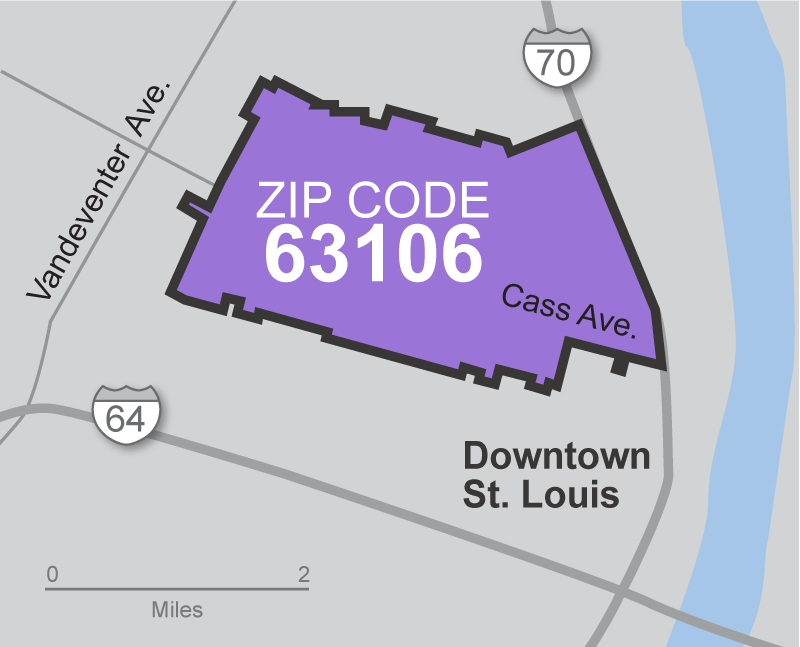

Preservation Square is in the city’s 63106 ZIP code, which ranks last in the region in social determinants of health. Those born in this ZIP code had a life expectancy of 67 years as of 2010, and the scourge of the virus has added to health challenges for many.

Nichols, 65, was raised in the area and attended Central High School, during which time she began a 45-year history of employment. That ended in 2016 when she decided that her arthritis was too debilitating to continue working. So, she used money in a retirement account, disability benefits and a pension to step away, which was difficult considering the active and social life she had led.

“When I retired, I was sad,” she said. “I wasn’t ready, but my body said it was time.”

Not long after Nichols left the workforce, her mother became her focus. It was a reality that hit hard when dementia became evident early in 2019. Nichols lost her sister to a heart condition in 1998 and her father to cancer in 2013. She became the critical link to her mother’s care.

Seeing her in generally good condition on Mother’s Day was an uplifting moment. But she knows that having a relative in a nursing home is a danger amid the pandemic. An employee at Grand Manor died of COVID-19 in April. Others have tested positive at the facility.

Never a homebody

Nichols has her own health issues to monitor. Aside from arthritis, she has asthma, which makes her think long and hard about going outside.

“I don’t have it real bad, but when it’s hot I don’t go outside,” she said. “When it’s 85 or 90 degrees, I notice. And when the rain comes or it’s humid, it will let you know. But I’m living. Some people are in worse shape than me.”

Nichols never has been a homebody, which makes staying inside during the coronavirus era a difficult task. She got her first job when she was 15. She worked at Stouffer’s Riverfront Inn and then spent a brief time at Homer G. Phillips Hospital as a nurse’s aide until it closed.

Nichols then spent nearly 15 years at Boatmen’s Bank and 10 with the Federal Reserve Bank. She spent the last 16 years of her working days with McCormack Baron Salazar, which owns Preservation Square.

Her challenges increased on March 23 with the city’s stay-at-home order. Nichols has filled days in her apartment with a routine: take a shower, make the bed, open the blinds, have a protein drink, check on her mom, watch “Gunsmoke” then the news, call a friend from church and her neighbor, then more news.

The urge to get out finally led Nichols to call a cab to go to a pedicure appointment in late May, with a mask at the ready. Another day she got a ride to Walmart and took her spot in a long line outside the store. She was allowed to move to the front when people noticed she was walking with a cane.

“I mostly just stay in my little apartment,” she said. “I just rest and be glad I’m alive. I might stand on the porch with a mask for 10 or 15 minutes and go back in. I go to the doctor. I can’t go to church anymore. That gets to me.”

One chance she had to see some friends and relatives came when a cousin on her father’s side died. She attended a small service. But what Nichols really wants is to have more time with her mother, who is her second-oldest living relative, behind a 92-year-old aunt.

‘We got happy’

Nichols was taking care of her mother at her home for a while in 2019 as she went in and out of a hospital. In January this year, Willie Mae Nichols was admitted to DePaul Hospital. She was transferred to a nursing home in St. Charles briefly before Nichols had her moved to the city. That was weeks before COVID-19 began spreading across the area.

She explained to her mother why she was unable to visit more frequently. Sometimes Nichols is unsure whether her mom fully comprehends what she is told. Concerns for her health have only increased. One night Nichols said she received a call from a nurse at Grand Manor who said her mother had fallen out of bed earlier in the evening.

Not long after that, Nichols called to schedule a visit and was told the residents were on lockdown. Her mother now can only leave her room to sit in the hall while wearing a mask. Because her mother doesn’t have a personal phone or one in her room, they are unable to talk unless it’s in person.

One month after Mother’s Day, Nichols went to deliver more clothes. Two nursing home employees arranged for her and her mom to talk using FaceTime — Valerie standing outside the main entrance and Willie Mae in her room.

“They didn’t drop the rule about visiting in person,” she said. “It was sad for both of us, but we got happy. She said she loved me. She said, ‘I’m ready to come home.’”

Focus on 63106

Among a population of 11,221:

50% live below poverty line

45% live without a vehicle

50% live with a disability

- Future home of National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

- Old site of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, where a small hospital/clinic is promised.

- Several St. Louis Public Schools, including historic Vashon High, the Flance Early Childhood Center, and charter schools.

- Affordable housing developments, including Carr Square Village, Preservation Square, Murphy Park, and Cochran Plaza.

- Numerous churches, including Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, Faith Temple, Progressive Missionary Baptist Church, St. John Missionary Baptist Church, and St. Stanislaus Kostka Church.

About Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity storytelling project, is telling the story of families in 63106 one by one over the course of the pandemic. This story first appeared the in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. You can sign up for e-mail notification of future stories and find an archive of other stories that have appeared in St. Louis media at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.org