After surviving a hail of gunfire coming from next door and in the midst of the pandemic, Kim Daniel seeks a refuge

This story first appeared at St. Louis Public Radio and was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. Additional support provided by the Buckingham Strategic Wealth Pillar Grant Program and the St. Louis Press Club.

By Richard H. Weiss

Executive Editor

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

A nonprofit racial-equity storytelling project

Kim Daniel harbors a modest dream. It was first born of youthful imagination, then deferred because of her fragile health and uncertain financial situation. She has now reimagined her dream, out of fear and desperation.

In her dream, Daniel packs her most essential belongings, turns over the keys to her two-bedroom apartment in Preservation Square, gasses up her compact SUV and heads south down Interstate 55. She exits right onto Arkansas State Highway 118, then right again onto Highway 64B, motoring straight through the center of Earle, Arkansas, arriving at an abandoned, weed-shrouded lot at the western edge of town.

Earle hardly qualifies as the Promised Land. It’s an impoverished community about 30 miles west of Memphis, Tennessee, that’s home to about 2,500 people, most of them African Americans.

The vacant lot there is the property Daniel visited last month. When she arrived, she found one-sixth of an acre, a rusted septic tank, barren utility poles and a well-water pump that could be used if anyone wanted to build there again.

What recommends it, at least to Daniel, is the price – just $555 – and the prospect that a program operated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture might subsidize her efforts to build a home there. What also is enticing is the 279 miles of separation between that property and Preservation Square, where she currently lives in fear.

Daniel was someone with few options in 2003 when she moved into Preservation Square, which was then known as O’Fallon Place.

“With public housing you get no choice,” she said. “I applied to the St. Louis Housing Authority hoping to get into the Murphy Park apartments because it was newer and nicer, but I received a letter in the mail stating I was approved for O’Fallon Place. Upon viewing this apartment, I hated it. But what recommended it was that I did not need a deposit. My rent was $77 a month, and it would be ready in time for me to have surgery and then return to the apartment for my recovery.”

For the next 17 years Daniel made the best of it, and she became a resource and sounding board for her neighbors.

But an incident that occurred in the wee hours of April 16 left her rattled as never before.

Daniel was sitting at her sewing machine making COVID-19 masks when she heard the report of an automatic weapon just beyond her front door. Daniel dived to the floor and crawled on her belly to her bathroom. Her actions were well-advised, as one bullet pierced the wall at approximately eye level, pinging off the dining room light fixture, redirecting and embedding in the ceiling.

Panicked and afraid, Daniel called the police … and waited … and waited for their arrival. She called 911 again. Finally, 90 minutes after the shooting, two officers arrived. One of them entered her apartment. Despite the pandemic, Daniel said, this officer was not wearing a mask. Still, he took her account.

It appeared there was a misunderstanding. Michelle Woodling, public information officer for the St. Louis Police Department, confirmed that police did get a call at the time that Daniel cited, but added that it was logged as the caller refusing police contact. Daniel remembers saying on the first call that she did not want her name used, but very much wanted the police to respond. The police spokesperson said the department could not confirm whether the officer entered Daniel’s apartment without a mask but added that the decision on whether to wear personal protective equipment is up to officers, based on social distancing guidelines.

After the officer left, Daniel recalled: “I wanted to regain some sense of safety, so I made a pallet on the hall floor. That seemed to be the best way to stay safe, and I called my son. We talked for a while, and he sent me a video to watch on meditation, and I tried to fall asleep.”

No luck with that. Instead, she began to formulate a plan.

With no assurances that police would find the shooter or take that person into custody, Daniel decided she would load up her SUV with necessities and hit the road, at that point, destination uncertain.

Before leaving, she sent an email to Denois Beckum, the property manager for Preservation Square, which is owned by McCormack Baron Salazar. Daniel described the gunfire and then wrote:

“Ms. Denois, I have dwelled in this apartment since 2003, making seventeen years, but I am sooo ready to leave, I simply cannot afford it, therefore I ask, will you please have this problem removed? Just 5 years ago, I endured nearly the same incident, due to the exact same neighbors. I love the little ones over there (in the apartment where the shots were fired), and I have created many events for them, tutored them and engaged them in multiple ways, but I cannot get through to the parents, and I am tired. I will be 54 this year, and with my heart condition, I cannot take much more.”

Feeling trapped

Daniel has long been recognized as the go-to person if any family member had a problem. But if something were to happen to her, Daniel said, “there is no one readily available. No one to count on, no one to be at my beck and call …”

But, as it turned out, Daniel did have family members willing to come to her aid. Stephanie Dorsey, a cousin from Texas, happened to be in St. Louis and called to check in with Daniel.

“I ended up breaking down in tears,” Daniel recalled. “I couldn’t stop crying. So she came over and sat with me.”

Dorsey called a friend who had a connection with Marriott. He booked a room for Daniel, and Dorsey put the charge on her credit card.

“It’s only right,” Dorsey told Daniel. A few years ago, Dorsey found herself stuck in a dead-end job at a discount store, despite having recently graduated from college with a degree in accounting. She had applied for numerous positions but hadn’t gotten any response.

At the time, Daniel was doing some administrative work for the Internal Revenue Service. Surely the IRS could use someone like Dorsey. So, she worked with her cousin to refine her cover letter and resume. Daniel saw that Dorsey’s cover letter lacked personality. “Dorsey needed to tell a story,” Daniel recalled. And within weeks, Dorsey had landed a job with the IRS in Houston, where she has worked for the past four years. “She says she wouldn’t have that job without me,” Daniel said proudly.

Dorsey’s generosity only provided a stopgap. On her own nickel, Daniel stayed several more nights in a less expensive hotel in St. Charles County. During the day, Daniel kept up her work with the St. Louis AmeriCorps VISTA program, editing and rewriting a manual on trauma-informed tutoring. She also works as a volunteer with young people through YourWords STL, a nonprofit that helps area youth develop writing skills through one-on-one tutoring and workshops.

Since April, Daniel has focused her attention on finding a place of her own, where she is less likely to fall prey to violent neighbors or have to rely on interventions from the police, property managers or family members. “I need to know the process of purchasing a house,” she said. She already knew from previous forays into the real estate market that it would not be easy. “Banks are always telling me, ‘You have excellent credit but insufficient income,’” she said.

Daniel’s research led her to a USDA program that encourages investment in rural communities with populations under 35,000.The agency could facilitate a loan, and she would not be required to come up with a down payment.

Photo: Kim Daniel

“Rural living is perfect for me,” Daniel said. “I don’t like people anyway, not a whole bunch of them. People ask me, ‘How do you feel about quarantine?’ I’m a natural-born hermit.”

Long ago, Daniel lived in rural Arkansas and was quite comfortable there, but due to a congenital heart defect that has nearly taken her life several times, Daniel required ongoing medical attention. Physicians in Memphis told her that St. Louis was her best bet for the specialized medical care she needed. So Daniel returned to her hometown and took the first housing accommodation to become available. She has felt trapped ever since.

What is high risk?

Earle has a troubled history and certainly could use some investment. The town is approaching the 50th anniversary of a 1970 race riot, when a group of white people armed with guns and clubs attacked a group of unarmed African Americans who were marching to city hall to protest the town’s segregated school system. Five Black residents were wounded in the melee.

Daniel is familiar with Earle’s history. After the riot, the mechanization of cotton fields, a series of tornadoes, the exodus of young adults and the passing of senior leadership, the town suffered greatly, she said. “Earle is wasting away. Without reinvestment, it may well return to prairie land and pasture.”

That would be of no great consequence to Daniel, as prairie land and pasture are what she longs for, along with a safe, affordable place to call her own.

While she is attentive to the social issues currently roiling the nation, Daniel is more taken with an approach that isn’t surfacing on social media or cable news. It’s an economic solidarity concept for African Americans that Claud Anderson outlines in a book and on a website called PowerNomics. Anderson, who served in the U.S. Commerce Department during the Carter administration, and earlier as an adviser to former Florida Gov. Reubin Askew, counsels African Americans “to pool their resources so that they can produce, distribute, and consume in a way that creates goods and wealth.”

Anderson’s ideas intrigued Daniel, but so did those of other thinkers. She also doesn’t mind sorting and sifting through what for most would be mind-numbing government documents, which is how she became interested in the USDA’s program.

If somehow she could figure out how to put the programs and the concepts together, Daniel would have her family members pool their resources, buy some land and leverage it to make investments that would sustain the family for generations to come — the American Dream.

Daniel recognizes that creating a base for such a dream in Earle, of all places, is unlikely. What recommended it was the setting and the $555 price tag.

But in other ways it made no sense.

Her son and granddaughter live in Florissant, and her father is in Overland. Another son is in prison in Alabama, but his wife and their two daughters call O’Fallon, Missouri, home. If she were to leave, Daniel said, “I would be sentencing myself to seeing my family even less often than I do now with this pandemic going around.”

Moreover, what if Daniel got sick? The nearest hospital is 30 miles away. Could she prevail on a friend or acquaintance to help her?

Weighing heavily on her also are the children of Preservation Square. For many of them, Daniel is a surrogate grandma. Just a few months ago, though it seems like years, the children would run to Daniel for hugs. She thinks about 8-year-old Makiya, 7-year-old Baby Tony, 5-year-old Aariah and Don-Don, and so many others.

Along with the hugs, they could expect to get lemon-drop cupcakes, which Daniel makes with a vegan recipe — no butter or eggs. On holidays, the kids look forward to a block party with lots of food and drinks, and a bouncy house to boot. Daniel and a women’s group she belongs to — Ladies Night Out — organize the event and foot the bill.

When Daniel sees the children now, they come running for a hug. But because of the pandemic, she has to stop them in their tracks.

“I shout, ‘corona, corona, corona,’ So they’re like, ‘corona?’” she said. “I’m like, ‘Yeah, corona. I’m a high-risk person.’ They’re like, ‘What is high risk?’”

The dream deferred

On Friday, July 3, Daniel took a calculated risk. She masked up and ventured out to Soulard Market to pick up a lamb shoulder. Then she went to Fields Foods for crowder and purple hull peas. She wanted to make a grand dinner for her dad, who was turning 82.

“I dropped them off Saturday, but due to COVID fears I left them on the front door, rung the doorbell and waited on the lawn for him to open the door,” she said. “He was more than grateful.

“As for the rest of July 4th, it was quite uneventful. Well, that is not true,” she paused and then said, “It was eventful, if gunshots, firework explosions and dumpster fires are newsworthy.”

This week, Kim Daniel picked up where she left off, returning to her apartment in Preservation Square while continuing to look for a way out, wondering when the time might arrive for her and all those in her circle of love and concern to gain their purchase on the American Dream.

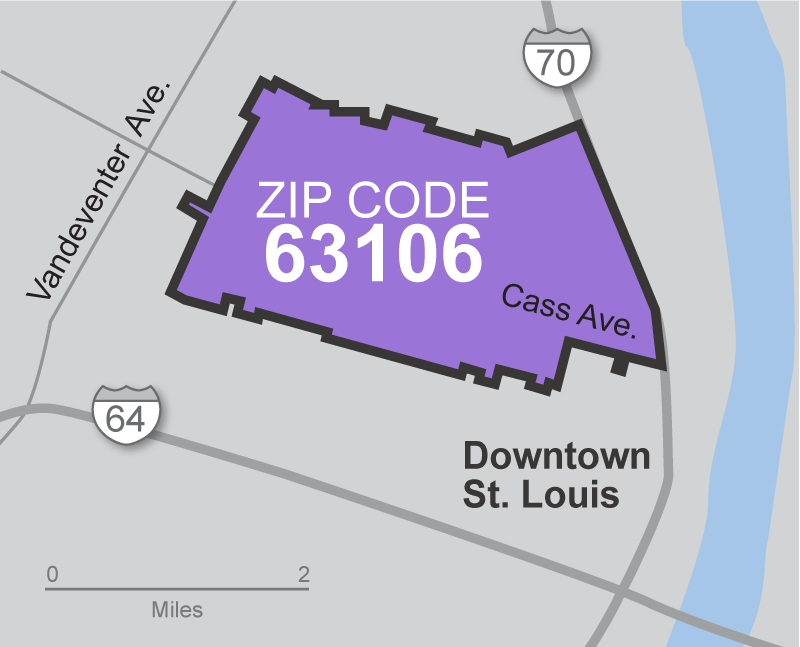

Focus on 63106

Among a population of 11,221:

50% live below poverty line

45% live without a vehicle

50% live with a disability

- Future home of National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

- Old site of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, where a small hospital/clinic is promised.

- Several St. Louis Public Schools, including historic Vashon High, the Flance Early Childhood Center, and charter schools.

- Affordable housing developments, including Carr Square Village, Preservation Square, Murphy Park, and Cochran Plaza.

- Numerous churches, including Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, Faith Temple, Progressive Missionary Baptist Church, St. John Missionary Baptist Church, and St. Stanislaus Kostka Church.

About Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

This is the second chapter in the story of Kim Daniel, which first appeared at St. Louis Public Radio. Daniel, 53, is coping with the pandemic in a neighborhood plagued by chronic illness and much shorter life spans than those in predominantly white neighborhoods. After surviving a hail of gunfire coming from next door, Daniel is desperately looking for a new home. Yet she hesitates to leave the neighborhood where many of the children see her as a surrogate granny. Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity storytelling project, is telling the story of families in 63106 one by one over the course of the pandemic. You can sign up for e-mail notification of future stories and find an archive of other stories that have appeared in St. Louis media at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.org