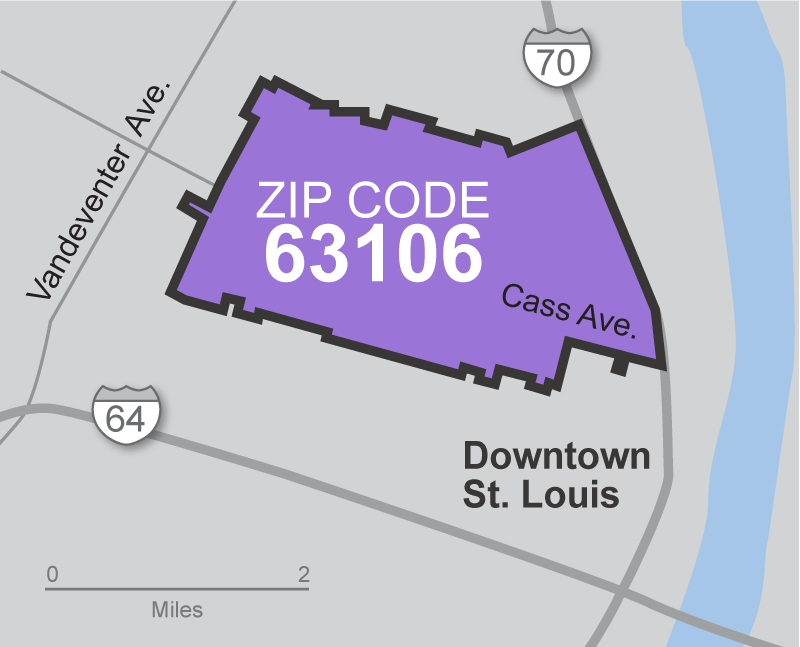

In the time of the pandemic, Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson (BFBF) , a nonprofit racial equity storytelling project, has been shining a light on the lives of people in zipcode 63106, one of St. Louis’ most vulnerable communities when it comes to the social determinants of health. In doing so we have partnered with St. Louis media to share these stories. This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. Additional support was provided by the St. Louis Press Club. It originally appeared at St. Louis Public Radio, Feb. 6, 2021. Click here to watch Daniel recount her experiences living in 63106 at a Zoom forum sponsored by the Jewish Community Relations Council.

By Richard H. Weiss

It was hard to think of a word that aptly described the world of hurt that Kim Daniel has inhabited these past few months.

Turning to Google, a noun surfaced. It is one rarely used in print or in everyday conversation. But Daniel agreed it sums up her life.

Excruciation — a state of acute pain, suffering, agony, hurting — a symptom of some physical hurt or disorder.

In the past four months, Daniel has lost seven family members ranging in age from 22 to 81; three to COVID-19, two to strokes, another to heart disease, and a young cousin to homicide.

At the same time, Daniel can tell that her health is declining. “I’m not so well, yeah,” Daniel said in a Zoom interview on Jan. 31. “I did a stress test in December, but I already knew that I was struggling … getting up, getting dressed, heading out to work. It’s taking more and more effort to do the simple things.”

Daniel lives in Preservation Square, a neighborhood a mile northwest of downtown St. Louis. I have been staying in touch with her for nearly a year now as part of Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson’s 63106 Project.

Our nonprofit racial equity storytelling project has focused on families in 63106 in the time of the pandemic because researchers have identified it as the region’s most problematic when it comes to the social determinants of health. One notable data point from researchers at Washington University and St. Louis University showed that the average lifespan of a baby born in 2010 would be 67 years old, compared to 85 for an infant in 63105, which encompasses mostly white and wealthy Clayton. And this, of course, was before COVID-19 came along.

Daniel is among the most vulnerable in her very vulnerable neighborhood. Now 54, she was born with a congenital heart defect that has taken her to death’s door several times. She lives in a neighborhood where gunfire is common. Last spring when the pandemic was just taking hold, a neighbor fired an automatic weapon inside his unit, with one of the bullets piercing Daniel’s wall.

Daniel took a COVID test in November, which thankfully came back negative, then visited with her cardiologist in December. Going on the symptoms Daniel described, she remembers her doctor saying, “Well, Kim, do you think it’s your health or the side effects of this Coronavirus,” meaning, as Kim put it, “the atmosphere of things.

The doctor seemed to be suggesting that Kim was coping with “chronic stress,” which can come about as a person with few resources tries to cope with difficult circumstances.

The National Institute of Mental Health says in one of its fact sheets that chronic stress “can disturb the immune, digestive, cardiovascular, sleep, and reproductive systems. Some people may experience mainly digestive symptoms, while others may have headaches, sleeplessness, sadness, anger, or irritability.” (A short video produced for the St. Louis Beacon, the former nonprofit online news organization that later merged with St. Louis Public Radio, demonstrates why disease falls hardest on marginalized urban communities.)

Physicians recommend engaging in a lot of self-care activities to reduce stress. But Daniel can’t find much time for a respite. She needs to work. One of the few good things that has happened in recent months is that she landed a job at the Flance Early Learning Center just seven blocks from her front door. Daniel started work in October as Flance’s family and community support liaison.

Within days, Daniel was making a mark, said Tami Timmer, Flance’s executive director. Timmer had met Daniel years earlier while working in another capacity. Timmer said that when she came to Flance a year ago, “I knew we needed someone with Kim’s vision. I kind of wrote the job description with her in mind. But she was somewhere else. Then, COVID happened. And it was like the heavens opened and she came to us.”

Timmer said Daniel initiated a program called PITCH, which stands for Parents If Talking Can Help. The goal is to encourage Flance families to think about ways to help each other and people in the neighborhood. The first session started inauspiciously with just a few parents showing up. But they had interesting ideas to help families. One was for a “drop and shop.”

Parents, staff and supporters were called upon to create a second-hand store for the holiday season where families could bring their used items and then find gifts among the used items other families had brought. The collections grew bigger over the weeks as Daniel and her small cadre of parents started leveraging social media.

“One day we had two huge SUVs full of gorgeous stuff — much of it brand new — toys, clothes,” Timmer recalled. “Then we had to keep postponing the date for the event because of quarantining. But Kim even played that to our advantage, as it gave people more time to donate stuff.

“People were so grateful and so thankful. I don’t even know how many lives we touched,” Timmer said.

The success of drop and shop, along with Daniel’s distanced interactions with parents and children, provided balm for her during a tough time. By Christmas, Daniel had already lost four family members, three to COVID-19 and one to a stroke.

Then at year’s end, a sledgehammer fell. On Dec. 30, her brother, Darius Seymour Daniel, 46, was rushed to Christian Northeast Hospital after suffering myocardial arrhythmia. He was placed on life support but died on Jan. 8, leaving behind his wife, Kelly Daniel, and their three children, Darius II, 15, and twin daughters Kamille and Kellsy, 12.

COVID-19 isn’t the only disease that falls most heavily on minority populations. Others do as well, including heart disease and stroke. In fact, the American Heart Association says cardiovascular disease is “a primary cause of disparities in life expectancy between African Americans and whites.”

Her brother’s death seemed so unfair. Danny, as she called him, had taken good care of himself. Though suffering no symptoms of heart disease, Danny stayed away from pork and beef. He also had gotten into a fitness regimen, dropped 65 pounds and had kept the weight off for the past seven years.

It seemed so random. But then so many things had been that way throughout 2020. A bullet had missed Kim last spring, but another bullet found a cousin on a street in Indianapolis. Kim learned of that death and one of another family member on the day of Danny’s memorial service. Despite the devastating events at the end of 2020, a bright spot surfaced on the horizon.

Most of Kim’s neighbors had avoided infection, and now the vaccine has come to town. The day before our Zoom interview, the city administered more than 1,800 first doses to city workers and residents at Union Station.

“Kim, have you been vaccinated?” I asked.

“No.”

“Are you going to get the vaccine?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because there is no history with this. And at least the one thing I can say, every piece of medication that I am on, has a documented history of results. This is too early, too soon, too new.”

Few public health experts would find Daniel’s skepticism surprising. Local public health experts Angela Brown, Bethany Johnson-Javois, Herb B. Kuhn and Dr. Will Ross, writing in the St. Louis American on Jan. 30, cited a study saying that Black people were “the most reluctant group by far” to want to get inoculated when vaccines became available.

“The root cause of medical mistrust is founded in atrocities such as the government-sanctioned Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, with pernicious effects that are perpetuated through generations,” the authors wrote. “It should come as no surprise then that fewer than half of Black Americans trust a government-sanctioned vaccine developed at ‘warp speed.’”

Still, these public health experts, three of whom are people of color, say it’s important for everyone to take the vaccine just as soon as they are eligible. So in speaking with Daniel, I persisted with my questions.

“Have you asked your doctor about whether you should or shouldn’t get the vaccine?”

“No. I won’t ask him because I’m not going to take it.”

“Don’t you want his advice?”

“I appreciate doctors and what they do, especially those who are willing to take the time to listen to me and will respond accordingly. But for me, in my life, the doctor’s opinion is not the final opinion, so I don’t.”

“Well then, who do you trust?” I asked.

“Myself,” Kim Daniel responded.

Kim Daniel will share her experiences in a Zoom forum on economic inequity sponsored by the Jewish Community Relations Council and a group of interfaith partners at noon Feb. 10, 2021. You can register by clicking on this link: https://zoom.us/meeting/register/tJYqc-CuqDgjG9Rgj-4-EJMWk8SDWcr2SHjB

More of Kim Daniel’s observations are on her blog: https://sistasistasister.wordpress.com/

Focus on 63106

Among a population of 11,221:

50% live below poverty line

45% live without a vehicle

50% live with a disability

- Future home of National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

- Old site of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, where a small hospital/clinic is promised.

- Several St. Louis Public Schools, including historic Vashon High, the Flance Early Learning Center, and charter schools.

- Affordable housing developments, including Carr Square Village, Preservation Square, Murphy Park, and Cochran Plaza.

- Numerous churches, including Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, Faith Temple, Progressive Missionary Baptist Church, St. John Missionary Baptist Church, and St. Stanislaus Kostka Church.

About Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

This is the first chapter in the story of Ebony Smith-Thomas. Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity storytelling project, is telling the story of families in 63106 one by one over the course of the pandemic. You can sign up for e-mail notification of future stories and find an archive of other stories that have appeared in St. Louis media at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.org