Though many consider the vaccine the answer to our pandemic prayers, Steven Jones isn’t so sure.

By Jeannette Cooperman

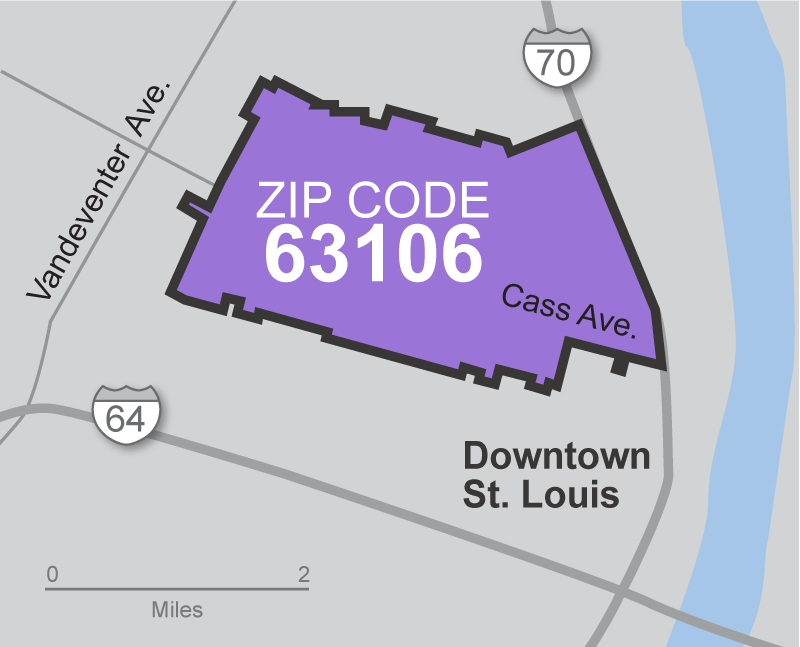

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity project, is telling the story of families in 63106 during the pandemic in various local media outlets. This is the fourth chapter in Jones’ story, which have been appearing online at St. Louis Magazine.

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

By Jeannette Cooperman

Working from home (still) in a quiet little town surrounded by farmland, I count the days until I am old enough or lucky enough to get The Vaccine. And then I think of Steven Jones, who I was assigned to follow through the pandemic because where he lives, in the city ZIP code of 63106, is anything but quiet, and access to health care is an Olympic obstacle course, and many of his neighbors have had to keep working with the general public, their faces just inches from contagion every day.

I call to see if he has registered for the vaccine.

He hesitates.

“Overall, vaccines are great,” he says. “Specifically, I have a problem with how fast they pushed it, the red tape that they cut through to get it done. They usually say it takes two to five years of getting it out to people, getting the data back, and seeing if any short long-term effects are happening. But if the first people we are giving it to are the people who are on the front lines — I understand, it’s necessary, you give the weapons to the people that are on the front lines, but we don’t even know if those weapons even fire correctly or they’re gonna backfire.”

The way these new vaccines work gives him pause, too — using RNA, they script the body to produce a spike protein that will trigger production of antibodies without actually making us sick.

“I’m not a doctor or anything,” Jones says, “but I remember in basic biology, the big difference between a vaccine and a bacteria is that the virus changes when it goes from host to host. So if Person A gets it and gives it to Person B, it will go from COVID-19 A to COVID-19 B. How do you do the whole spectrum of Point A to Point B with one vaccine? You have to constantly keep changing it.”

I mention Moderna adding a booster shot to be on the safe side, but Jones is making a different point: He thinks we should trust our immune systems instead. “My body is supposed to see something foreign and create antibodies to fight it off,” he says. “Now, if my body can’t fight it off, then it’s a problem.”

Which is the chance I’m not willing to take. What tilts Jones the other direction is first, he has a seizure disorder, so he’s not sure how his body will react, and second, he does not trust the U.S. government or the corporations behind the vaccine.

“Here we are at a point where a company has said, ‘Oh, we came up with a vaccine’ just in perfect time in between a double whammy of a double impeachment–slash–gonna get a new president,” he says. “There’s a lot going on.”

If vaccination does become necessary, he wants to know how much it will cost. I assure him that it is free; there might be fees in some occasions but most insurance should reimburse them.

“What insurance?” he retorts. “Who has insurance?” He ran into a brick wall with his disability coverage, he adds. “I talked to my counselor and she basically told me it was ‘because every time you had a seizure, you wasn’t going to the ER and getting a doctor to say you had a seizure.’ So every time I have a seizure when I’m home by myself, after I wake up after the seizure, you want me to call 911 and go to the hospital to quote-unquote confirm it and then leave the hospital and find my own way home? Just because your paperwork says if you’re between 18 and 50, it’s a lot more difficult? ’Cause y’all just don’t want to pay.”

The outrage fades, and he gives a worn-out chuckle. “If there’s a rock in the way, my mom says pray about it, but these are mountains and boulders, and it’s getting annoying!”

The shelter-at-home precautions that drive others crazy, though, don’t bother him at all. “I’m OK with being stuck in the house—I’m a house person anyway,” he says. “People have been getting antsy because they haven’t been able to get out, but they were going to work, buying stuff, selling stuff, let’s just be honest. It’s the kids that are getting on people’s nerves. You’ve got moms that never wanted to be moms, and now, ’cause the kids are home, they’re losing their mind.”

I seize the segue to ask about his four daughters, whom he adores. Does he want them to get vaccinated?

Nope. Not yet, at least. And their two mothers agree with him. “We don’t know the effects yet,” he points out. He mentions an antacid that was lavishly prescribed, then recently withdrawn: “It destroyed people’s insides. It’s been ten years before y’all ever figured it out. In 2030, what if we find out the young girls fresh out of school start getting cancers or can no longer have kids? It’s too late.”

(Later, an infectious disease physician will tell me that any vaccine’s effects show up in one to three months, not years later.)

“I can understand if your children are going to the school and you don’t feel comfortable if your child gets vaccinated and mine doesn’t,” Jones continues. “OK, cool. Home learning. And that’s another thing—they didn’t even give us free wifi for this! It could be the same network, just give us a password, with firewalls so our children can’t see porn, no TikTok, no social media. Just a student portal. Now I’m not a genius, they’re not paying me for these ideas, and it don’t take long to come up with them. So you have people that can come up with these Armageddon swings around the Moon to get rid of the asteroids, and we can’t solve these basic life problems?”

As our conversation turns to politics—which is inextricable from the vaccine—I ask what he made of the attack on the Capitol.

His first thought was, “Are we seriously in the land of the free, home of the brave? I don’t know if they’re trying to incite a civil war to happen,” Jones says, his voice heavy with frustration. “I don’t know what they’re trying to incite. We all know that if it had been people from the Mike Brown protests or people kickin’ in Foot Lockers to steal shoes rioting to crush the capitol of the country, those people wouldn’t have made it out alive. It’d be body bags out there. It would have been the military out there. They brought the military for Mike Brown. You can’t bring the military for Washington, DC? How am I supposed to personally feel about that?

Hope for the nation’s future often rests on its young people, but they are Jones’ biggest worry. They hear this country is a republic and think it means Republican, he groans. “I mean, we didn’t have direction when we were that young, but we had some semblance of a foundation somewhere. We had Captain Planet, so we cared about the planet. We had Bill Nye the Science Guy, so we kinda knew about science. These kids grow up with Sponge Bob. Nothing of substance. And they move with the wind. Everything is TikTok or one of these social media platforms. So you have a lot of people that are running full steam ahead without looking.”

Rather than chirp something Pollyanna, I duck back to the vaccine—has his mother gotten one?

“Not that I know of,” he says. “She works from home. But knowing how my mom is Captain America, she probably will. She’s a strong believer, and she believes whatever happens, happens for the best. My mom’s a soldier. She will follow orders. And I respect that. And”—we’re talking on the phone, but I can tell he’s grinning—“that’s why I never wanted to go into the military.”

He and his mother go back and forth often: She will murmur, “Son, those are the rules,” and he will come back, “When the rules only apply to certain people, then the rules no longer matters. Like chess. My knight can only move in an L shape, but when this person plays, he can move it anywhere on the board? Now we have got to change the game completely.”

Unable to disagree, I return to the vaccine: Does he have any friends who’ve gotten it?

“I have quite a few female friends who are CNAs, nurses, nurses’ aides, or work in home healthcare, so, front-liners. One has gotten vaccinated, and she had to take off the week after, because she was so sick. The other one that got vaccinated, she hasn’t had any abnormal reactions except pain to the site.”

He brings up the patchwork of precautions: “I mean, we’ve still got basketball games going on. Are you telling me that they don’t have to wear masks? The NBA’s still going strong, wrestling is still going strong, boxing is still going strong, but the people who nine-to-five it, we’ve been struggling.” The message he takes is “‘If you have money, we will make sure you are good, but if you are a bottom feeder, we don’t care.’ And that really pushes on the people who labor to keep America going, across all spectrums and races. We feel disrespected.”

In the background, a door opens. Abelina Jones has come home.

“Mother, are you getting the vaccine?” Steven calls, and I hear a firm single syllable.

“For the record, my mama says no,” he tells me, then hands her the phone.

“For me, the vaccine has not been tested enough,” she says, her tone matter-of-fact. “It has not been long enough to maybe get the adverse reactions dependent on your race or your underlying health conditions or other medicine that you might have taken. So I’m gonna have to wait a while.”

When she leaves the room, Steven and I talk about the economic fallout of the pandemic.

“Because we are such a consumer-based society,” he says, “the only way to get our economy going is, we gotta spend. But if we don’t have money coming in, we can’t spend. The people that are getting rich are the people that have I would call valuable assets. And I’m not talking Bitcoin, I’m talking real estate.”

The other day, he saw a meme on Facebook about the $600 economic stimulus payment. Stretched over a year, “it broke down to, like, $1.62 a day,” he says, “and they played it right next to an ASPCA commercial where they ask you for $20 a month for a dog.”

For now, Jones has a solution for the legislators who argued about a $600 versus a $1,200 payment: Just take the money from state lottery programs. “Also, we could stop putting money behind NASA for a couple years. Because we ain’t gonna make it to Mars if we can’t get past COVID.”

Focus on 63106

Among a population of 11,221:

50% live below poverty line

45% live without a vehicle

50% live with a disability

- Future home of National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

- Old site of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, where a small hospital/clinic is promised.

- Several St. Louis Public Schools, including historic Vashon High, the Flance Early Learning Center, and charter schools.

- Affordable housing developments, including Carr Square Village, Preservation Square, Murphy Park, and Cochran Plaza.

- Numerous churches, including Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, Faith Temple, Progressive Missionary Baptist Church, St. John Missionary Baptist Church, and St. Stanislaus Kostka Church.

About Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

This is the first chapter in the story of Ebony Smith-Thomas. Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity storytelling project, is telling the story of families in 63106 one by one over the course of the pandemic. You can sign up for e-mail notification of future stories and find an archive of other stories that have appeared in St. Louis media at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.org