I am Richard Weiss, a journalist, who worked 30 years at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Since 2005 I have been on my own as an editor and writer, focusing most of the time on social justice issues. A few years ago, I created an enterprise, now a non-profit, called Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a racial equity storytelling project. Our mission is to tell the story of local African-American families that have struggled over generations in our town to gain their purchase on the American Dream. These were long-form stories researched, written, photographed, and video-recorded under my supervision with a diverse team of more than a dozen professionals, and now we number more than 20.

The stories were aimed at creating a culture of understanding and empathy in our community that would support the racial equity recommendations of the Ferguson Commission. We felt fortunate and gratified when mainstream media outlets including the Post-Dispatch, St. Louis Public Radio, KTRS-AM, St. Louis Magazine and the St. Louis American reproduced and promoted these stories in one form or another for their audiences.

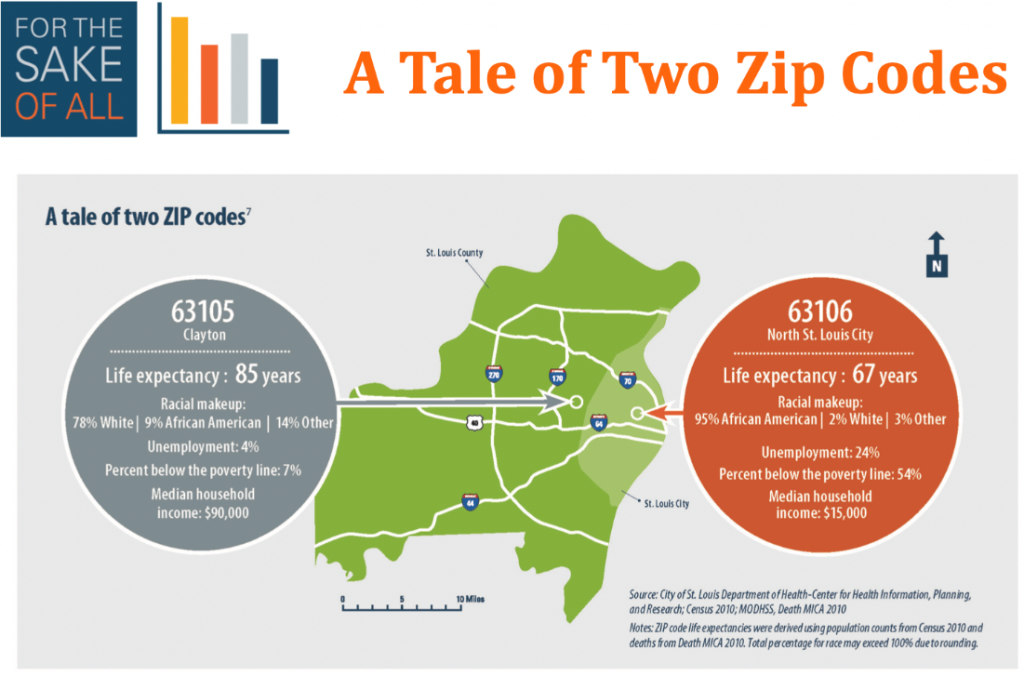

Then late this past winter the pandemic came along and I knew we had to at once switch gears with our project and put it into overdrive. Accordingly, we created the 63106 Project, with a focus on families living in neighborhoods identified as having the most problematic social determinants of health. Many in our town are familiar with the For Sake of All Report, produced by academicians and researchers at Saint Louis University and Washington University’s Brown School of Social Work. So much excellent research and data crunching went into that report, but there was one number that stood out in particular. A child born in 63106 in 2010 had a life expectancy of 67; a child born in 63105, just six miles away, one digit removed, could expect to live to age 85. An 18-year differential.

And this was before the pandemic.

Well we all have those numbers, and those data points. And, as grim as they are, they are gift to this community and to policymakers in terms of how to address inequities, and systemic racism.

What our project attempts to do for the community is to connect the heart and the mind. We now know what it is. We also know why it is. But here we are telling readers how it is in these particular neighborhoods, for these particular people. So far eight families have stepped up to share the “everydayness” of their experience.

The first was Kim Daniel, who lives in the Preservation Square neighborhood and copes with a congenital heart defect that has taken her to death’s door several times over the course of her 53 years. But she has never been more terrified than in recent weeks. Not just by COVID-19, but also a neighbor who fired an automatic weapon in a home adjacent to hers, with a bullet piercing an adjoining wall. The police responded, but for whatever reason he remains free and Ms. Daniel is looking desperately for another place to live.

Living nearby is Tyra Johnson, 32, pregnant, and the single mother of three. As Aisha Sultan wrote in a story under our sponsorship that appeared in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Ms. Johnson is too scared to let her kids play outside their home.

Then there’s Steven Jones, also living not far away. According to Jeannette Cooperman’s account for St. Louis Magazine and under our sponsorship, Steven is the single father of four, 33 years old, dealing with a physical disability. Steven lost his job in a pandemic-related downsizing.

This project is unique in that they are not one and done, or as some might call it … drive-bys. We will write new chapters in the lives of Ms. Daniel, Ms. Johnson, Mr. Jones and the others as long as the pandemic continues.

Our stories portray people up against pernicious systems, but don’t think for a minute they are defenseless. They are resourceful and smart, and come up with work arounds that are pretty amazing.

When the pandemic led to cancelled classes for Tyra Johnson’s children, Madison, 4, and Meegale, 5, she set up a strict daily schedule for their distance learning.

She maintains a white board with the home-school daily schedule, down to the minute.

9:05 to 10:15: Circle time, reading, writing and homework packets sent from school.

10:05 to 10:25: Healthy snack and free time.

10:25 to noon: Math and problem solving.

Meegale was already reading at a first grade level even though he’s in kindergarten. She is not going to let her children fall behind.

Ms. Johnson starts her day around 7 a.m. by pulling up the verse of the day on her Bible app. She meditates and prays on it for about 15 minutes. Then she appeals directly to God.

“Lord, thank you for waking us up,” she says, “protecting us and giving us another day’s journey. I’m glad about it. You didn’t have to, but you did. Amen.”

None of the people in our stories turned out for the protest demonstrations in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd. They are of course almost entirely sympathetic to the Black Lives Matter movement, but they have so much on their plates that it’s impossible for them to participate. So, in a sense, they are truly among the unheard. The work that we are doing here is distinct in many ways, but there is nothing new under the sun. We are particularly inspired by Isabel Wilkerson, a Pulitzer Prize winner, a MacArthur Fellow, and the author of “The Warmth of Other Suns.: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration”

Not long ago, Wilkerson was interviewed about her book and her work on NPR. She described how when African-American families arrived at their destinations from the South they were shunted to the wrong side of the tracks and hemmed in by all manner of laws and public policy prescriptions.

This is what happened in our town, too.

Wilkerson believes changing laws and public policy is important, but it won’t be accomplished in a world without empathy. Or as she puts it, “radical empathy.”

Wilkerson says that means putting “ourselves inside the experience of others, to allow ourselves the pain, allow ourselves the heartbreak, allow ourselves the sense of hopelessness that they are experiencing…

“And so,” Wilkerson said, “I view myself as on kind of a mission to change the country, the world, one heart at a time…I feel as if the heart is the last frontier, because we have tried so many other things.”

So we join Isabel Wilkerson in her work. We offer the stories from the 63106 Project and those to come as a means not just of changing laws but of changing hearts.

Richard H. Weiss

Founder/Executive Editor

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

A Racial Equity Storytelling Project