Kim Daniel, age 53, lives with a lifelong congenital heart defect

This story, which first appeared at St. Louis Public Radio, was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center with additional support from the St. Louis Press Club.

By Richard H. Weiss

Executive Editor, Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

A nonprofit racial-equity storytelling project

Kim Daniel has stared death in the eye more times than she can count. But this coronavirus has her more than scared. ‘“It’s intimidating,” she says. “I don’t walk out the door without a mask, gloves, baby wipes and rubbing alcohol.”

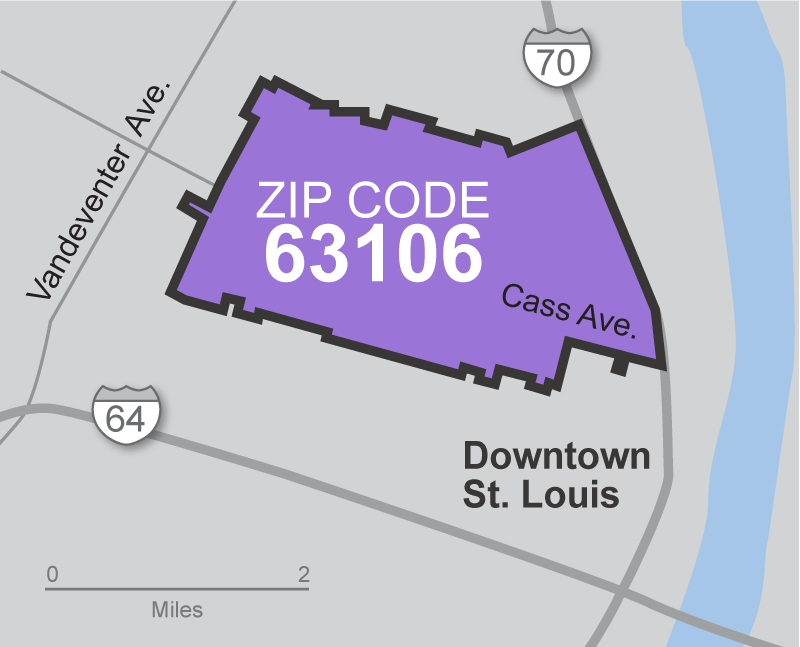

Kim’s door opens into a tidy two-bedroom apartment in an affordable housing development called Preservation Square. It is located just a mile west of downtown St. Louis, in a zip code that has been identified as ranking last in our region for social determinants of health. A lot of factors go into that ranking, but the key one is that, on average, people living in 63106 will die sooner than most anyone else in metropolitan St. Louis. The life expectancy of a child born in 63106 in 2010 was 67 years old, according to data from the census and the St. Louis Department of Health. That compares to 85 years old in 63105 – which would be Clayton, the St. Louis County seat just six miles to the west.*

Residents in 63106 die younger because they suffer from higher rates of chronic illnesses like cancer, heart disease and diabetes. They have less access to health care, nutritious food and fresh air. Higher crime rates are a factor too, not just because of the physical harm crime brings, but because of the stress it imposes on immune systems. Crime also makes residents fearful to venture outdoors and to public spaces where they can enjoy sunshine and recreation.

Now add to this toxic stew the looming threat of a pandemic that impacts everyone but will fall most heavily on African-Americans.

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a non-profit racial-equity storytelling project, is telling the story of families in 63106 one by one over the course of the pandemic.

Kim Daniel’s story is one of as many as 10 that will be shared with mainstream media in St. Louis for what will likely be months to come. You can watch this space for further episodes in Kim’s life and find an archive of other stories at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.com.

Kim comes to the pandemic as a seasoned veteran. Kim was born with a congenital heart defect. “They (the doctors) said I wouldn’t live to my first birthday,” Kim recalled. ”I made it. They said I wouldn’t live to age six,” Kim recalled. ”I made it.”

At age 17, in 1985, Kim dropped out of Beaumont High School after learning she was pregnant. The pregnancy nearly cost Kim her life; she went into cardiac arrest in her ninth month. But doctors resuscitated her and performed an emergency C-section. And that’s how Terrence came into this world.

At age 24, it seemed Kim’s time had come once more. She suffered a cardiac arrest while undergoing a cardiac catheterization. But the medics were able to bring her around once more.

“The doctor told me then, ‘If you don’t lose weight, you’ll be dead by age 35. Right now I weigh 219 pounds (80 pounds heavier than she was at 24) and I am still here.”

Her dieting aside, Kim knows how to take care of herself – and others. Her resourcefulness and determination may be what sees her through the pandemic. Despite her health issues, Kim went on to earn a GED – and didn’t stop there. She is a life-long learner. If she needed to know something, she picked up a book, or went online. That’s how she learned to save, understand government benefit programs worked and invest her money wisely. That’s how she was able to put food on the table for Terrence, and later his little brother, Michael. And that’s how she was able to afford a car when many of her neighbors must rely on public transportation.

The Preservation Square neighborhood is in the middle of the 63106 zip code and includes a public elementary school, an early childhood center, a convenience store, and is accessible to Metro bus routes. Photo: Wiley Price/St. Louis American

Given these characteristics, it’s perhaps not surprising that for years, Kim was a caregiver for her extended family. She not only raised her two children but also helped watch her sister’s child and her aunt’s four children.

When her two sons were children, Kim relied for a couple of years on food stamps to feed them and herself. She started up with food stamps again in 2004 and continues to receive SSI (Supplemental Security Income), which provides a stipend for basic needs for low income citizens with disabilities. But she has always sought work and has held a variety of jobs, from hotel housekeeper, to home healthcare aid, to school bus driver (her favorite). She is currently starting her second year in the St. Louis AmeriCorps VISTA program. Under its aegis, she is working with Urban Strategies, an organization that helps bring resources to underserved neighborhoods in St. Louis and nationwide.

Marlene Hodges, a longtime community organizer for Urban Strategies, says Kim is a master at outreach, excelling at organizing social events for residents in Preservation Square. “You give her a task and she gets it done,” Hodges said. Kim was starting to build an advisory council that would give residents a stronger voice in the future of their neighborhood when the coronavirus outbreak brought her effort to a temporary halt. Now she is working from home, editing and rewriting a manual on trauma-informed tutoring.

Kim, whose health is fragile, says she never leaves her apartment without masking up and putting on gloves. She took a few seconds to produce a selfie without her mask for this report.

Kim is definitely trauma-informed. She has seen and experienced more than her share in the neighborhoods where she has lived and within her family, too. Her eldest son, Terrence, a Navy veteran, was arrested not long after this discharge in 2011 for participating as the driver of the getaway car in a bank robbery in Auburn, Ala. That led to a 22-year sentence that he is serving at the state’s Fountain Correctional Center. Kim is a strong believer in having her son face the consequences. But now he is facing more than just doing time, as prison inmates are considered very much at risk for contracting the coronavirus.

No infections have been reported to date at Fountain, which is about 50 miles northeast of Mobile. But few tests have been performed. And Alabama officials were bracing for an outbreak, with a prediction of as many as 185 deaths among a statewide prison population of 22,000, according to a report obtained by AL.com.

“No one should be faced with a life-threatening disease especially when they don’t have the opportunity to do anything about it,” Kim said. I am just hoping that the Alabama Department of Corrections will test all their employees and inmates so they can separate the sick from the well to serve out their time without being infected.”

Kim’s younger son, Michael, 32, is faring better, but is nonetheless at risk too. Also a Navy veteran, who saw action in Iraq and Afghanistan, Michael is now an essential worker. Each day he rises at 1 a.m. to head over to an Amazon warehouse in Hazelwood. There he loads more than a dozen pallets of packages to take to rural post offices in eastern Illinois, about a 400-mile round trip. This is all done with masks and distancing and with Michael assiduously wiping down his truck. But Michael is an independent contractor, which means that he not only provides his own vehicle but gets no medical benefits. He has no health care coverage.

Michael also recently lost his home to foreclosure. He is living with his father at his home in Florissant. What little money he can put aside will go to pay for tuition at a parochial school for his 12-year-old daughter, Mi’kehael, who currently is staying with her mom.

Kim wants to help her family, and anyone she can during this crisis. She has been a caregiver all her life to family, friends, and even strangers. She has always provided the answers either by providing sage advice or hands-on help. But who will provide the answers for Kim, should her heart begin to fail, should she contract the virus?

“If I fall ill,” Kim says, “there is no one readily available. No one to count on, no one to be at my beck and call, no one to manage my bills.

“My only alternative is to remain healthy.”

Focus on 63106

Among a population of 11,221:

50% live below poverty line

45% live without a vehicle

50% live with a disability

- Future home of National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

- Old site of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, where a small hospital/clinic is promised.

- Several St. Louis Public Schools, including historic Vashon High, the Flance Early Childhood Center, and charter schools.

- Affordable housing developments, including Carr Square Village, Preservation Square, Murphy Park, and Cochran Plaza.

- Numerous churches, including Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, Faith Temple, Progressive Missionary Baptist Church, St. John Missionary Baptist Church, and St. Stanislaus Kostka Church.

About Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson is a nonprofit racial-equity storytelling project that shares the stories of African American families and the challenges they have faced over generations in gaining their purchase on the American Dream. This story, which first appeared at St. Louis Public Radio, is one of a series on families living in the 63106 zip code amid the pandemic. Readers are invited to find an archive of stories like this one and join the email list for this project by visiting BeforeFergusonBeyondFerguson.org