By Zach Bayly and Richard H. Weiss

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

“I made it.”

This is what Ebony Smith-Thomas murmurs each time she awakes from the surgeries that keep her heart beating.

That Ebony has “made it” to her 38th year, qualifies as more than a minor miracle.

At age 2, Ebony was diagnosed with lead poisoning. Doctors told her mother, Debbie, and father, Zachary, she likely would suffer from cognitive impairments the rest of her life. But by midlife, Ebony had managed to earn a bachelor’s degree and dual master’s degrees in business management and information systems. She would go on to serve for nearly 14 years with the nation’s largest operator of campus bookstores, while also raising two sons, Clayton, 5, and Khamari, 16, and parenting two beloved nieces, Mykinzi, 20, and Mareah, 23, through their adolescence. She is now helping “Kinzi” and “ReeRee” chart successful career paths of their own.

And then, five years ago, Ebony found herself at death’s door. Each time Ebony awakes and says “I made it,” she adds another chapter to her experiences that arguably can be tied to systemic racism.

It’s easy to connect Ebony’s childhood experience to what many public health practitioners and social justice advocates have identified as environmental racism.

Civil rights leader Benjamin Chavis is credited with introducing the concept in the 1980s, which he described as “racial discrimination in the enforcement of regulations and laws, the deliberate targeting of communities of color for toxic waste facilities, the official sanctioning of the life-threatening presence of poisons and pollutants in our communities …”

Ebony would qualify in the “presence of poisons” category. She was one of thousands of St. Louis children afflicted with lead poisoning because of their exposure either to lead-based paint, tap water running through lead pipes or because they lived in a neighborhood with air-borne contaminants.

Ebony’s malady — as her mother Debbie Thomas-Smith later determined — came from eating paint chips from a window sill in the apartment where her family was living on the campus of Saint Louis University. Like any child, she was drawn to the window because she liked playing outside. Debbie hadn’t noticed at the time that Ebony was also attracted to the sweet taste of those paint chips. It was only after some time that Ebony began crying and complaining that her fingers hurt that Debbie sought medical attention for such an unusual symptom.

That diagnosis came in the mid-1980s as St. Louis was struggling with a plague of lead poisoning falling most heavily on families of color in the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods. Lead poisoning actually became a problem much earlier, around the turn of the century, but was not identified in the region as a pernicious toxic source until the 1950s with a medical journal article identifying a “seasonal incidence of leading poisoning in children in St. Louis.”

Almost every year since the ‘50s, public health officials were able to document at least one case of a child dying from lead poisoning, with hundreds more identified as having severely high levels of lead in their blood that affected their cognitive abilities and their behavior. Mass screening programs began in the 1970s and advocacy groups organized protests to pressure regional leaders to do more. The St. Louis University School of Medicine organized a Get Out the Lead Conference in 1971, and by 1972 the city had established a lead poisoning evaluation center. Around that time, the city introduced stricter lead-abatement statutes. More funding and staffing would follow in the 1980s.

In the early 2000s, city officials would proudly say that they were making significant inroads against lead poisoning. The lead poisoning rate in St. Louis had fallen 71 percent from 2000-2005, Jeanine Arrighi, then the city’s manager for children’s environmental health, would tell Bob Joiner, a health reporter for the St. Louis Beacon. (Note: To find the referenced story in the link, scroll down to Part Seven.)

But not long after that, the city’s public health department underwent budget cuts. By 2014, Arrighi had been reassigned. The city would have many fewer people to address compliance with lead poisoning mitigation. Still there was some good news. Older buildings with lead issues either were getting demolished or repainted with non-toxic paint. Manufacturers were getting the lead out of their products.

Even so, the racial disparities around lead poisoning continued to be dismaying. In 2019, the Interdisciplinary Environmental Clinic at the Washington University School of Law provided a report to the community. Citing figures from 2016, researchers reported that Black children were “2.4 times more likely than white children to test positive for lead in their blood and account for more than 70 percent of children found to suffer from lead poisoning.”

“There have just been a history of racist decisions over the years that have impacted the health outcomes of people in our city,” Arrighi said in a recent interview.

“I think of the housing stock that people have been forced to live in that were in poor repair and not well maintained. I think about the Mill Creek Valley where so many African-Americans lived but then moved for urban renewal. They were led to believe new housing developments would replace those existing in the neighborhoods that lacked proper plumbing and services and that the residents would be able to return to their communities and businesses. The public housing built in the late 1950s and early 1960s still had the high probability of containing lead-based paint. My own introduction to the issue with lead-based paint was due to regulations and programs in the late 1980s and early 1990s to address deteriorating lead-based paint in public housing.”

Many children with lead poisoning exhibit no immediate symptoms and so the toxic effects are given time to take a toll on brain function. They are nearly impossible to roll back once they do. Even with early intervention, some lead remains in the body, seeping into the bones where it can linger throughout life. Much less is known about the long-term impact on people, now adults, who have been diagnosed with lead poisoning during their childhood.

In the immediate aftermath of her daughter’s diagnosis, Debbie remembered asking the university to eliminate the lead contamination in her apartment and to provide support for her daughter’s care. She said officials never responded in a meaningful way. She contacted an attorney about the issue, but said he quickly lost interest.

The apartment was in the old Coronado Hotel, built in the 1920s. The hotel at 3701 Lindell, which was designed by architect Preston J. Bradshaw along with other significant structures along that boulevard, fell on hard times in the 1960s and closed. The university purchased the Coronado in 1964 to use for student housing, then closed it in 1986. The once-grand building stood vacant and fell into disrepair until developers Amrit and Amy Gill purchased the property and began reviving it in 2002 with apartments, a restaurant and event spaces. Many SLU students have lived there since.

University officials have been asked to see if they can find records relating to Ebony and her family’s stay there. Debbie and her family moved in while she pursued her education as a paralegal at the law school across the street. Looking back, and knowing what she knows now, Debbie finds it ironic that some at the university ‘s medical school were at the forefront of lead poisoning mitigation, while other university officials turned a blind eye to her plight.

“Not just a blind eye,” Debbie said in a recent interview, “the SLU On-Campus Housing Staff treated Ebony’s health crisis like their mouths were sewn shut too.”

Fortunately, Ebony rebounded strongly. This was in part because of quick intervention once her symptoms were identified and her mother’s strong advocacy for her with health care workers and educators. She sailed through school and on to college, earning high marks along the way. “My mom never let me (use lead poisoning) as a crutch,” Ebony recalled. “When computers came out, I probably was the only kid who had a computer. She got me Hooked on Phonics. She said, ‘Your number one job is getting your education.’”

Back in the day, it was common to use the phrase “mentally retarded.” As she grew up, Ebony sometimes heard it applied to her. It carried a special sting, because Ebony was smart and knew it. She is resilient and determined, too.

“I did college because I was told that I wouldn’t be able to go to college,” Ebony said. “I felt like I had to prove the doctors wrong. And I did.”

In 2003, Ebony landed a job with Follett Education Group. She worked in the bookstore Follett operated at Harris-Stowe State University while earning her bachelor’s degree at the university. By 2010, while working on earning dual masters degrees at Webster University, Ebony had been promoted to store manager.

The work was complicated and stressful, requiring at once great people skills and IT know-how. But it would fill her with joy to see the students who she supplied with their texts freshman year come into the store years later to pick up their mortar boards and gowns.

***

Then in 2016, on a warm day in late May, Ebony’s world turned upside down. It had been just two months since Ebony birthed her second child, Clayton – or Clay-Clay as family and friends affectionately call him. Ebony, Khamari Clay-Clay, ReeRee and Kinzi were living in an apartment in the Hyde Park neighborhood in north St. Louis when the air-conditioning failed. They packed up and moved in for what they hoped would be a short stay with Ebony’s mom and dad at their home a few miles west in the Jeff-Vander-Lou neighborhood. That night, Debbie noticed her daughter sleeping fitfully and heaving with a dry cough. “There’s such a thing as walking pneumonia,” she told Ebony the next morning. “And that could kill you.”

At first, Ebony remembered thinking, “Well, nursing new moms generally don’t sleep all that well.”

But Debbie had always been on high alert when it came to her youngest daughter’s health. Family members called her Dr. Webbie Smith, as in WebMD because as Ebony put it, “if she doesn’t know (about an illness) she is going to find it and figure it out. She reads and reads.”

When it comes to her health, Ebony says, “There’s nothing I feel like my momma don’t know.”

It turned out, Dr. Debbie/Webbie had been right.

After several hours at an urgent care center where tests confirmed pneumonia, Ebony was taken to Barnes-Jewish Hospital. There more tests revealed something worse, peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), a life-threatening illness that affects women who are either in the last month of pregnancy or first few months after delivery.

“I am glad you came in,” Ebony recalled a physician telling her, “because your heart was going to eventually stop pumping.”

Ebony battled the illness for three years, until yet another health crisis — a blood clot traveled to her lung. “It felt like elephants were sitting on me,” Ebony said. Over the next several weeks, Ebony lost 60 pounds. In October 2019, doctors put her on a list for a heart transplant, which she received in August 2020.

“I made it,” Ebony said when she awoke from the surgery that had lasted nearly 23 hours.

Just three weeks later, Ebony would undergo open heart surgery to address a blood clot in her new heart.

“I made it,” Ebony would sigh again.

In the meantime, both Ebony and Debbie were doing their homework. Ebony had taken part in a support group of women with PPCM, where she learned a lot more about the illness, but also had to deal with a lot of sadness because some members of the group were dying.

One thing she learned was that PPCM falls more heavily on people of color. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2017 reported that African-American women “presented with more severe cases of PPCM, recovered less frequently and took at least twice as long to recover despite apparent adequate treatment when compared with their non-African American counterparts.”

Ebony resolved that once she got better she would start a non-profit that would educate, help and support women with PPCM, and urge others to become registered organ donors.

What Ebony has only recently learned is that there is also research suggesting that lead poisoning may play a role in cardiovascular disease even years after exposure.

So it’s possible — though it would be hard to prove — that Ebony dodged a lead-poisoning bullet three decades ago — only to have it circle the earth and take her down in the prime of her life.

Dr. Andrew White, a professor of pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine, who has treated children with lead poisoning, says that it’s possible that lead poisoning can lead to cardiovascular issues later in life. But he added much more research would need to be done to demonstrate a definite link.

“I think it’s plausible. Lead shares some properties with other atoms and molecules that are important to the heart, like calcium,” White said. “Calcium and lead can certainly compete with each other. But in reading the Lancet journal article that reported the link, they were looking at ischemic heart disease, which is really like heart attacks and which are distinct from PPCM. So maybe there’s no direct correlation … but maybe there is.”

Whether it’s lead poisoning or other factors that contributed to her PPCM and consequent heart transplant, this much is clear: Ebony can no longer work nor be as active in her children’s lives at least for a good long while.

Ebony is entitled to what the government offers to everyone regardless of race. In Ebony’s case it’s a mixture of Medicare and Medicaid benefits, which paid for her transplant and a good deal of her medical care. She also receives food stamps. But it doesn’t make up for the lost income from the job she had to relinquish, nor does it pay for the deductibles attached to her healthcare coverage.

Ebony’s cousin, Chantel Neal, who she calls “Fav,” put together a go-fundme site for her that to date has raised just over a thousand dollars. In the meantime, on her own Facebook page, Ebony keeps friends apprised of her journey: https://www.facebook.com/newheartwhodis/ and she promotes #letstalkppcm, a group that supports and informs mothers with the illness.

Ebony’s mom and dad, and cousin Misha Marshall, help out with childcare, so that Ebony can focus on regaining her health and spending quality time with Clay Clay, Khamari, and her nieces, ReeRee and Kinzi, as she is able.

“Because I have been in and out of the hospital for quite some time, I’m not always home. But I’m a parent. I want to stay in the loop,” Ebony says. “Whatever I could do to make my sons and nieces successful in whatever class that they are in I’m going to do that. I’m that type of parent.”

At times, Debbie says she sees her daughter sinking into depression. Along with everything else, Ebony is dealing with chronic kidney disease brought on by a common side effect to the drugs she takes to stave off rejection from her transplanted heart. She may be facing dialysis within a few years and possibly a kidney transplant.

Yes, Ebony admits she sometimes is on the brink of despair. But then she thinks about Clay Clay on the cusp of starting kindergarten and Khamari, just a year away from college. “They are die hard momma’s boys,” Ebony says. ‘’If nothing else, if I don’t even fight for myself, I got to fight to be there for them.”

Zach Bayly is a reporter and board member for Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson. Bayly attended Clayton High School and went on to Columbia University where he is currently majoring in education and Spanish. He was recently admitted to the Urban Teachers program where educators are trained to be culturally competent, accelerate student achievement and disrupt systems of racial and socioeconomic inequity.

Richard H. Weiss is co-founder of Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson and also serves as executive editor for the non-profit racial equity storytelling project.

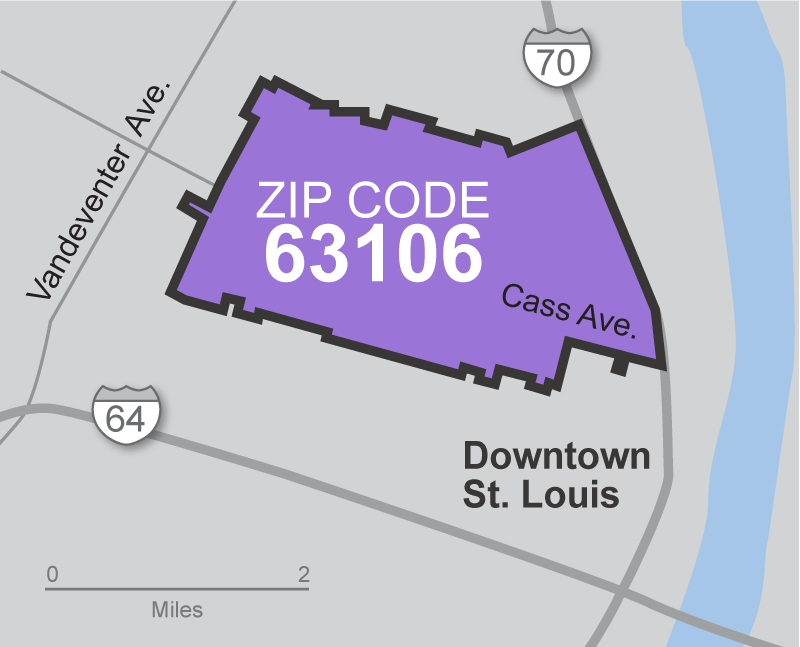

Focus on 63106

Among a population of 11,221:

50% live below poverty line

45% live without a vehicle

50% live with a disability

- Future home of National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

- Old site of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, where a small hospital/clinic is promised.

- Several St. Louis Public Schools, including historic Vashon High, the Flance Early Learning Center, and charter schools.

- Affordable housing developments, including Carr Square Village, Preservation Square, Murphy Park, and Cochran Plaza.

- Numerous churches, including Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, Faith Temple, Progressive Missionary Baptist Church, St. John Missionary Baptist Church, and St. Stanislaus Kostka Church.

About Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson

This is the first chapter in the story of Ebony Smith-Thomas. Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity storytelling project, is telling the story of families in 63106 one by one over the course of the pandemic. You can sign up for e-mail notification of future stories and find an archive of other stories that have appeared in St. Louis media at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.org